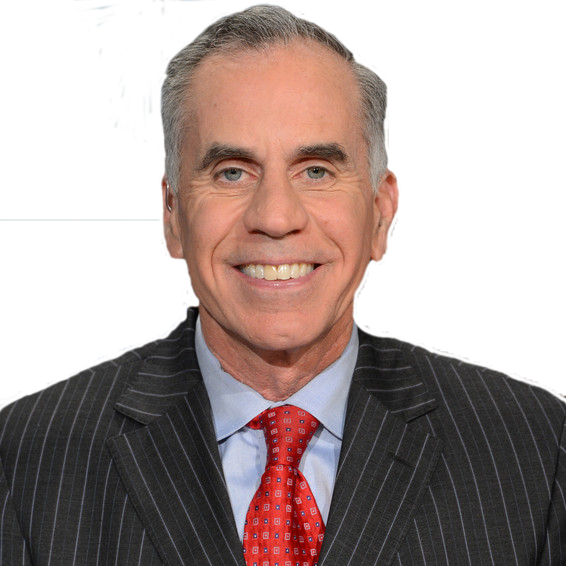

WRIGHT THOMPSON

Biography

A native of Clarkdale, Mississippi, Thompson studied journalism at University of Missouri, serving as a Missouri football beat writer and columnist.After his junior year at Missouri, Thompson landed an internship with the New Orleans Times-Picayune. He was hired by the paper upon graduating, and immediately became the beat writer for the LSU football team.

Upon leaving the Times-Picayune, Thompson joined the Kansas City Star where one of his role models, Joe Posnanski, worked. Thompson wrote weekly long-form feature stories ranging from 3,000 to 3,600 words.

In 2006 he joined ESPN, where has crafted many award-winning stories. Notably, he received the 2010 Scripps Howard Award for Human Interest stories. His work has been featured in Best American Sports Writing seven times, and his story, “Michael Jordan Has Not Left the Building,” was recently nominated for a 2014 National Magazine Award.

Interviewed by Josh Needelman and Phillip Suitts

I always wanted to be a writer. I knew that from a very early age.

I delivered newspapers when I was eight. I read a book called North Toward Home by Willie Morris. I read that and after I finished I was like ‘Okay, I would like to do that.’ He was the editor of Harper’s, one of the big inventors of new journalism, whatever you want to call it. So I mean, I wanted to write magazine stories – those kinds of stories. Sports was an accident. I was randomly assigned to sports by the college paper.

I just thought it was an amazing life, more than anything. It never occurred to me that people did that.

I was a sports fan. I mean, I was a normal sports fan. I liked a lot of teams, but I’m still not a huge sports fan. I can’t name all the Major League Baseball teams. I don’t know a ton about it.

I have an extraordinary amount of freedom and I work with really smart people. So I don’t-I feel no urge to go anywhere else. I don’t feel stifled by sports. I don’t feel like there’s a ton of stories that I’d like to tell that I don’t have the opportunity to tell. I just never felt restrained or stifled at all. I love these stories that we’re doing. There’s nowhere else I would ever want to go do it.

I get very selfish at times. I write about things that are interesting to me. Which are often very different. All of these stories, the thing they have in common is that they were somehow interesting. I feel like they’re all dispatches from a worldview.

Not to sort of cop out about it, but I don’t know how other people see stuff. I feel like most of sports writing is just sort of confirmation of a narrative. I feel like most of it is just the narrative. I don’t like that.

When you talk to someone who really knows about football, you realize that almost no one that covers football really understands what’s happening on the field. Every time you read a book, it’s behind the scenes. I recently read a book by a friend of mine, Nick Dawidoff, called Collision Low Crossers. Basically for a year and a half inside the NFL, he was just totally embedded with the Jets. If you read the coverage of that team, and then that read that book, it’s like the thing being covered is totally separate from the thing happening. You always want to write what’s really happening. Not sort of what it looks like from the outside.

Also, to be fair and honest about it, I write six to eight stories a year, and get to spend an extraordinary amount of time on them, and get to keep digging until I find that level of depth, or if it isn’t achievable, to kill the story.

And if you’re covering a team, you’re writing every day. Like in some ways, it’s not the person; it’s the structure of the job. If you took the New York Yankees beat writer and put him in my job, his stories would read with more depth and if I had to go cover the beat mine wouldn’t. Some of it’s the function of the job.

For a story I just wrote, I spent a week in Bosnia, and then a week in Germany, and then I’ll spend a week on my notes, and I’ll spend a week writing.

[On Johnny Manziel’s Dad]

I wish you could listen to the interview tape. I mean, it’s not even an interview, I just hung out with him all day. He met me in the driveway of his house, and was talking about Texas A&M before we got in the house. I didn’t ask him a single question. He had something (to say) and I was the one who came.

I went to the journalism school at the University of Missouri. The best part about it was that we had a group of people there at that time, who were all very talented and ambitious. There was a bunch of people there who pushed each other. So I was very lucky to fall in with that sort of thing.

I was the football beat writer and LSU beat writer for the New Orleans Times-Picayune. And I felt completely prepared to do that job because I had been the Missouri football beat writer at Missouri, and I felt totally prepared. I felt ready to go do it.

I wanted to go to the journalism school there. I didn’t want to go to Northwestern or Columbia because I thought it’d be too cold. And, it was really between the journalism school at Missouri or going and getting a liberal arts degree at University of Virginia. Willie Morris, who wrote that book, was friends with my Dad. Willie pushed hard for Missouri.

There are two reporting classes (at Missouri): intro reporting, and everybody covered either a minor Missouri sport or high schools. I covered Missouri baseball. I was a grinder. Still am. I sort of worked my way onto the beat.

The only job I got (after graduation) was because the sports editor was a Mizzou grad. Absolutely true. I applied to every single internship in the country after my sophomore year, and didn’t get any of them. And then I applied to every single one in the country after my junior year, and got one — at the New Orleans Times-Picayune. The sports editor was a Mizzou grad. And then he hired me. I’m certain that’s why.

We were very very lucky. We all got the Kansas City Star, so we all read Joe Posnanski almost every day. So we were all involved in sort of a low level Joe Posnanski impersonation all the time. I read old Sports Illustrateds. I’d go to the library and read old Sports Illustrateds. That’s what we did.

We’d read all of the Best American Sports Writing, we’d go read all of the SIs. We had free Lexis-Nexis. So we’d go and find all of the classic stories. And the internet existed in a way, and we could also do Lexis-Nexis searches, so we’d read like a week of (Los Angeles Times) Bill Plaschke.

We just read classics. It was sort of wonderful. We had plenty to read. The most important thing was to break news, break news, break news. That’s how I got jobs. I got an internship because I was breaking news on the Missouri football beat against major dailies.

And then I got my job in New Orleans because I was the intern and the Tulane beat writer went on vacation, and they fired the basketball coach and hired a new one, and I broke the hire.

The greatest sentence in the history of newspapers: University X will announce the hiring of coach Y at a 2 p.m. press conference today. That’s the greatest sentence in the entire world.

Kansas City was incredible because I wrote 3,000 to 3,600 words for Sunday’s newspaper every single week. For five years. I wrote most of them live (on deadline). I’d wake up Saturday morning and write it. And [I] just did it over and over and over again. And it’s just the best possible school in the world. I didn’t write a story longer than 4,000 words until I got to ESPN. I had 3,600 words down to a science.

I did big events and I was the takeout writer. We’d have a meeting on Monday. We usually would go have lunch at a place called Manny’s in Kansas City. It’d be me and Holly Lawton and [Mike] Fannin. And we would figure out what we wanted for that Sunday.

Fannin was huge on the Sunday centerpiece. Almost like in his head it was like the old Sports Illustrated bonus piece. Sort of like what was going to be the anchor of the Sunday paper was his obsession. And so [we’d] sit there Monday and figure it out.

We were flush with money then. It seems nostalgic now, but I’d usually be out on the road Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, come home Friday, wake up Saturday and write. I still smoked then, so I worked at a coffee shop across the street from my apartment, Rivermarket. I’d go there super super early, write, and then I’d take my laptop out to Fannin's house.

He’d edit the story and we’d cook big steaks and I’d usually just crash in his guest room, wake up the next day, barbeque all day, and watch football. And then we’d have lunch on Monday and do it again. We did that week after week after week for years.

It was awesome. It was very, very difficult, but it was the best possible training to write these stories I’m writing now. You have to make it work every week, so you have to learn how to find a story quickly, and trust yourself, and what to do, and what not do, and how not to waste motion.

So I became a very good outliner out of necessity because there wasn’t time for me to write my way through a story. If I messed it up, there wasn’t time to go back and do it again. So it all became about how to do it under the set of circumstances.

I completely trust myself. I can make a decision and just do it. And I’m not scared to completely change gears in the middle of reporting, or to follow it down a rabbit hole. I feel I have a pretty good sense of what will and what won’t work.

I remember the profiles. Like go do Peyton Manning better than anyone else is doing. Go do Steve McNair. I spent a week with an 8-man football team in Hope, Kansas, for a district playoff game and I lived in the house with the quarterback who knew that the rest of his life in this little town was going to be defined by this week.

A horse race track burned down in Eureka, Kansas, and it was this story about this town that was dying, and that the racetrack was the perfect metaphor for it because the highest attendance ever was on the day they opened. It’s been declining since literally the moment they opened the doors.

[On going to ESPN]

I got assigned to drive John Walsh around when I was in college because he received this award, and I just kissed his ass shamelessly, and then kept in touch. He’s a Mizzou guy, likes Mizzou people, so that helped.

They had an opening at ESPN and it worked out. I turned down some other jobs, like one or two columnist jobs. Essentially the thing that everyone wanted to be was a sports columnist. And I just sort of didn’t. It’s just boring to me. So this is what I wanted to do. I wanted to work at ESPN (The) Magazine or Sports Illustrated.

I love to write about place. The most important class I had in college was an English class. I actually went and found the teacher a couple years ago, just to thank her. It was ‘Place and the Character in 19th century American literature.’ We read Wizard of Oz, we read Huckleberry Finn. Those kinds of classes were very important.

I had an unbelievably great editor [at the Kansas City Star] in Mike Fannin. He really deserves the lion’s share of the credit. One of his great catchphrases was ‘Be literary, but hurry.’ I remember I was in Cuba trying to find Jose Contreras’ family and I was doing a bunch of other stories down there too since I was there, and it was just a bang for your buck, and it just wasn’t going well with Contreras’ family, so I called him.

I was trying to like undersell Contreras and oversell these other stories to make him take the pressure off for Contreras. Try to play mind games on him, which was never going to work in hindsight. He listens to all this and he goes “If you don’t find his family, don’t come home!”

I was knocking on the door of a crack house one time. It was like a real crack house; the front door was on hinges. I had to go up to the second or third floor and knock on the door of the family of this basketball player.

I think I was in a yellow Mustang rental car, which was very conspicuous. I called Mike and I was like, ‘This is a crack house, like a real crack house.” And he said, “I don’t care if you take two to the chest, you’re knocking on that door.” And then hung up. So it was very sort of high energy, high pressure. That’s what he was like. It was great. It just was turn and burn. What’s the joke? I write better than anyone who writes faster and faster than anyone who writes better. I mean, that’s all Mike Fannin.

I used to be really obsessed with the idea of the brass ring, the business card. You’ve got to go here, and what’s next. And I just don’t anymore.

I used to be obsessed with writing for Esquire, just because I loved to read Esquire. Now, I just like to read my friend’s stories in Esquire. That’s enough for me. I don’t have a burning ambition to be in a place. I just want to do each story well. That’s it.

Nobody gets hired to do (longform journalism) as their first job and no one is ready to do it.

You’ve got to write a lot of 1,200 word stories before you can write a 3,000 word story. You need to write a lot of 3,000 word stories before you can write 5,000. The difference and degree of difficulty and complexity of a 6,000 word story versus an 8,000 word story is staggering. It’s like a whole other thing. It’s exponential.

I only feel like in the last three years I actually know how to do this. I think you’ve got to read a lot and write a lot and make a lot of mistakes. I would not want to have to try to do my job without those years in Kansas City where comparatively speaking no one was watching.

And I didn’t have to make my mistakes in public, or on a high profile thing. You’ve got to write a lot of stories before you can. Gary Smith worked for a newspaper, like covered the Phillies, you know? They’re hard to do. I still sometimes wake up, my wife will laugh at me, I still sometimes go ‘I have no idea how to do this.’

When you’re a kid you think writing has to do with words and then you figure out that it doesn’t and that it has to do with structure. It’s architecture. That’s the whole job. It has nothing to do with words, really. It’s outlining, structure, it’s conflict and resolution.

Every single movie ever it’s the character confronts an obstacle and is changed by it. That’s it. That’s what all stories are.

Whether it’s ‘The Iliad’ or ‘Harold and Kumar go to White Castle.’ It’s all the same. It’s understanding that and understanding conflict and resolution. There’s a great book called Writing for Story.You know, John Franklin. I’m sorry if he’s like you’re friend, he comes across like a pompous ass in this book but it’s a great book.

It really is. I think he thinks it’s a religion, when it isn’t. But it’s the best thing on outlining I’ve ever read. That book changed my work life. It’s the first time it ever really made sense to me.

Now I go through notes, I outline and underline and I make note cards and reorganize the notes into like piles. And I cover walls of offices with post-it notes. I do whatever feels like is necessary to wrangle all of this information.

I’m outlining on the road during stories. I’m outlining constantly. Trying to figure what is the story, what is the story. That’s what I’m asking myself over, over and over again on the road. What’s the story? What’s the conflict? What’s the resolution? What’s the arc? What’s the narrative arc? What question are you going to ask at the beginning that you answer at the end. What’s the end? I like ends, I like hammers. I want the ending that kind of makes you sort of feel hollow briefly in your gut.

That’s a very difficult thing. What is it? Once you have the end, how do you structure the story so as to maximize its power? And do nothing over the course of the story that might diminish it. Protect the hammer. It’s a rare and beautiful thing. How do you protect it while you’re telling the rest of the story? I don’t know. I’m constantly thinking about that.

That’s the job. Words are just words. You know, people just write how they write. Outlining is the thing. Not everyone writes down an outline. My friend, Chris Jones, just writes. But he’s outlining in his head. So it’s the process of thinking about the story. So you know what it is and where it’s going.

The hammer. I wrote this profile on Michael Jordan. I knew the moment the thing with the Western happened at the end. I found out earlier that he falls asleep to Westerns, and the moment I heard that I was like that’s the end of the story.

Everything else about that became about making sure that was in no way blunted. That had maximum power. I wanted to introduce the idea of Westerns, I wanted to do it in a way that was funny, so that you set it up funny, so it wasn’t just foreshadowing, so it was there and then you have to come back to it later and repurpose it for your main point of the whole thing. It was the perfect metaphor. I didn’t want to do anything that blunted its power.

I must’ve rewritten that thing 30 times. It was all about protecting the hammer. And you’ve got to know you’re ending when you see it. It should almost always be an action that speaks to the metaphoric heart of the story. You start to figure it out.

[On planning a story]

I have something I’m interested in, or I wouldn’t have been drawn to it. I don’t ever seek to sort of prove a thesis. You have to be willing to follow it. But usually, I’m not trying to prove a point. There’s something that’s intriguing me, so I’m answering a question.

Everything that happens is good; there is no bad thing that could happen. It is what it is. I don’t ever sort of go into something trying to prove a thesis. I have a question that I want to find an answer to. It’s like if you look at a bunch of stories, they’re either profiles or quests. That’s really how a book is. A lot of quests.

And the reason they work is because they don’t read like journalism, like some editor cooked ‘em up. You know when they start asking this question that no one will really answer? When I go do a story about like racism in Italy, it’s because I read that news story, and was like what was going on.

And I went to answer a question that I actually wanted to answer. And the story works because the quest is real. And readers can tell the difference. When you read that story and it doesn’t work, it’s because that person writing it didn’t believe his own quest, so now you don’t either.

[How long do outlining and writing take]

It depends. It took me 20 or 30 days of long writing days to write the fly fishing story, and it took me three days to write Michael Jordan. Sometimes it goes fast. I wrote a thing about my dad at the Masters, and I wrote that in three hours. I just sat down and wrote it. Sometimes I go really, really fast. It just depends.

I’m being a little coy about stories not being about words. Because if you do some things with the outline, then you start worrying about words again. You want every magazine story to read like a short story that’s true. I read a ton of short stories. I read a lot of fiction.

Tim O’Brien. Gatsby. I love Hemingway. There’s so many. Everything from Stephen Crane, to Elmore Leonard, to James Ellroy, to Barry Hannah. Donald Ray Pollock.

We’re not splitting an atom, here. You show up and work hard and do your thing. You’ll figure out a way to get it done.

I’m like that with things that have nothing to do with work; I’m just like that. I get obsessed and I go down rabbit holes. I went through a phase where I learned everything there was about Samurai swords. I never wrote a story about it, I just wanted to know.

I’ll watch nine straight episodes of Top Gear. I’m just like that. And I’ve always been like that, since I was little.

In terms of staying motivated, I am as hungry now as I was 10 years ago. I don’t feel remotely satisfied or any sort of fulfilled, or like I’ve done my best work. I don’t feel like that at all. Last year was a really good year; I don’t want to hear about it. It’s done. What’s next? I don’t know, man. I don’t feel remotely safe or entitled to anything. I want to go earn it every day. When I don’t have that anymore, I’m done.

My favorite story I’ve ever written, absolutely, is on Dan Gable. That was my favorite. That’s absolutely my favorite. I felt like that’s the best I could do, right now.

[Parting comments]

Everybody always wants to know, how do you get the job you want. And I think it’s pretty simple, actually. It’s outwork the guy next to you. The hardest working guy at ESPN is Bill Simmons. Without question. I’m not Bill’s target audience; I think Bill’s a very, very good writer. But I’m not his audience.

Every single person who knows him has profound respect for his work ethic. I mean that guy’s a grinder. So you look at the difference between the people who are doing the cool things that everyone wants to be doing and those who aren’t.

You look under the covers enough and you’re going to find a grinder. You look at people on TV: Jeremy Schaap. Grinder. Tom Rinaldi: Grinder. Peter King: Grinder. Chris Jones: Grinder.

You show me the people who you want to be like, and they’re all totally different except for the fact that all of them work their asses off. Everybody. That’s it.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski Adam Schefter

Adam Schefter Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor Frank Deford

Frank Deford Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Bryan Curtis

Bryan Curtis Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga