My mother gave me the love of baseball. She was enamored with Jackie Robinson. It was a very momentous occasion. In 1947, she became an avid Dodgers fan, and passed that on to me. My dad was a fan of the Giants and Willie Mays. I listened to my mother more than I listened to my dad. I just love baseball.

It’s a great sport to write about, tell stories. It not only merges society, but it often leads society, as the breaking of the color barrier shows.

You integrate in ’47, and it takes the country 20 years to make it national law. It caught my attention. I wanted to learn about the people.

It’s a sport where you write about the people who happened to play, as oppose to writing about point spreads and X’s and O’s. It’s a sport that gives journalists probably more access than any other sport because they want to show the human face.

They want you to understand their errors, and to understand the human facet of the game.

You have to see the face of the pitcher who lost the no-hitter in the 9th inning with two outs. That’s what drives the sport. It’s the storytelling, and that’s what I love to do.

What I remember best about baseball growing up is that I used to tease my mom that she is out of my will because, when I was in elementary school, she got tickets to a doubleheader in Philadelphia: It was Jim Bunning and Chris Short against Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, and she took my brother because he was a boy. I was just like ‘OK, mom, thanks a lot.’

I love the Dodgers because of Jackie Robinson. He’s my hero. I don’t know how to say it any simpler than that.

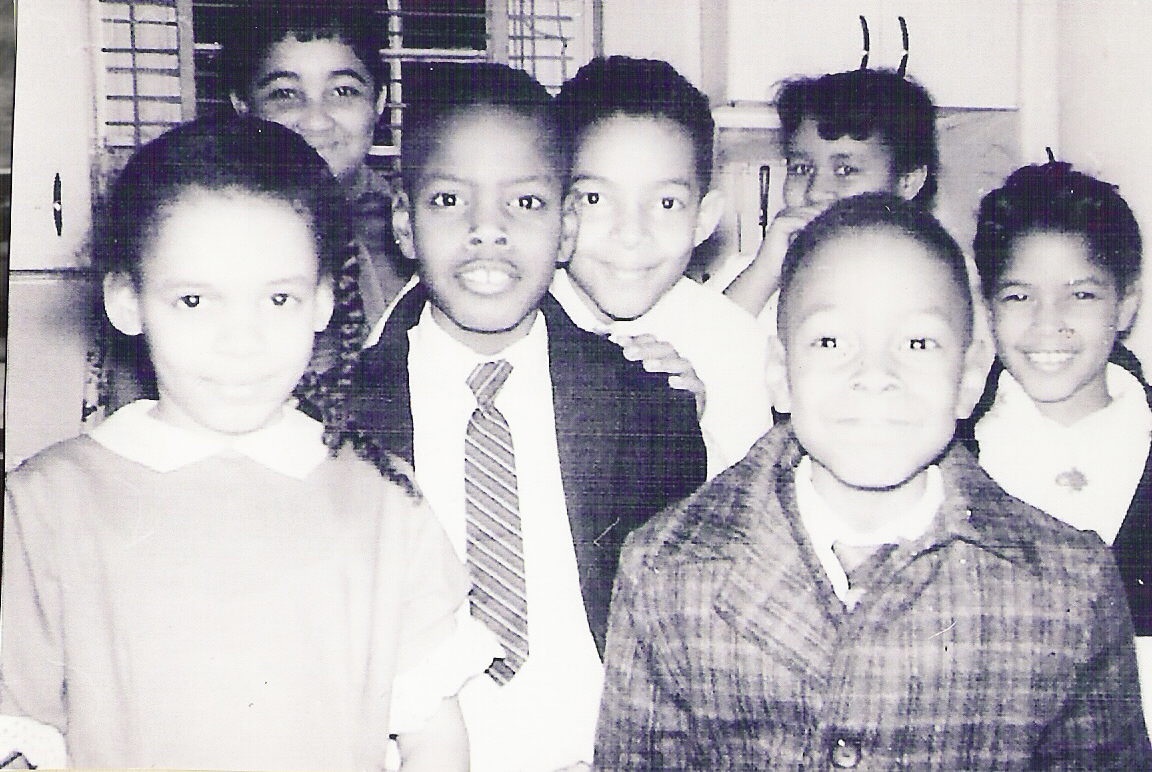

(Photo Courtesy of Claire Smith)

When I was in third grade, I attended St. James Elementary School, and the sisters gathered us up and took us into the basement where the church was and showed us a movie titled ‘The Jackie Robinson Story,’ starring the great, great Ruby Dee as Rae Robinson, and Jackie Robinson as Jackie Robinson. It’s not as bad as “The Babe Ruth Story”, but you know.

I just sat there as a third grader looking at these gorgeous men, knowing that it was really him. It wasn’t Gary Cooper, it wasn’t John Wayne playing Ted Williams; it was Jackie Robinson. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Wow, that is who my mother has always been telling me about.’ I just fell in love with him, and I never fell out of love with him.

The Dodgers always made it necessary to be a fan because if I wasn’t just falling in love with Jackie Robinson, it was Sandy Koufax. Like, wow, could you have more integrity than to walk away from the World Series rather than pitch on Yom Kippur? He was just drop-dead gorgeous and so good.

And then my boys came.

The Garvey era, Bill Russell, Davey Lopes, Ron Cey, Dusty Baker, just really good people. I was a really big fan, so I used to go down to Philadelphia, wait, and get autographs.

I got to know them, and they got to know me. To this day, we are still friends. It’s been over 40 years.

None of them disappointed me. I’ve heard horror stories about people growing up love a sport, and then meeting their childhood hero, and they turn out to be the devil’s spawn, drunks or racists. But, no one ever disappointed me. They were some of the best people I have dealt with in sports, even after their career.

I loved Dodger Stadium, the first time I saw it, and it took my breath away. It was all just so ideal. It was easy to be a Dodger fan. I never got to see Jackie play. He retired in 1957, rather than accept a trade to the Giants.

I never got to meet him, but I have become friends with (daughter) Sharon Robinson and (wife) Rachel Robinson. They are just beautiful ladies. His legacy is in such good hands with them. The first time I ever saw the home uniform was at the Pittsburgh All-Star Game in 1974. I sat with some friends of mine way in the upper deck, and I think four Dodgers walked out onto the field in their powder white uniforms, and I was just like, “Whoa, that’s so cool!” It was a wild time.

The first time I saw Dodger Stadium was in 1978. I flew myself out to see the playoffs against the Phillies. It was my first-ever work vacation, and that’s where I wanted to go. So I did.

I watched more than I played. I wasn’t very athletic, but my brothers were, so I liked to watch them.

I’m envious of the women today who grew up under Title IX. I remember just loving the game so much, that I used to have a transistor radio at my ear, while under the covers, trying to pick up stations.

I’m envious of the women today who grew up under Title IX. I remember just loving the game so much, that I used to have a transistor radio at my ear, while under the covers, trying to pick up stations.

I obviously couldn’t listen to Los Angeles, but that was my team. So, anytime they came east of the Mississippi, I would try to pick them up on the New York stations. I even listened to them in French coming from Montreal. Wherever they were, I tried to pick them up on the radio.

I could hear them in Cincinnati, I could hear them in Atlanta, obviously in New York, so I got to hear some of the legendary announcers. Jack Buck, Harry Kalas, Richie Ashburn, my friend.

So I listened, I taught myself how to keep score. I was also developing, unbeknownst to me I guess, somewhat of a writing skill. I could kill on a blue book when I got into college more easily then a multiple-choice test. I could write some of the best fiction in those blue books.

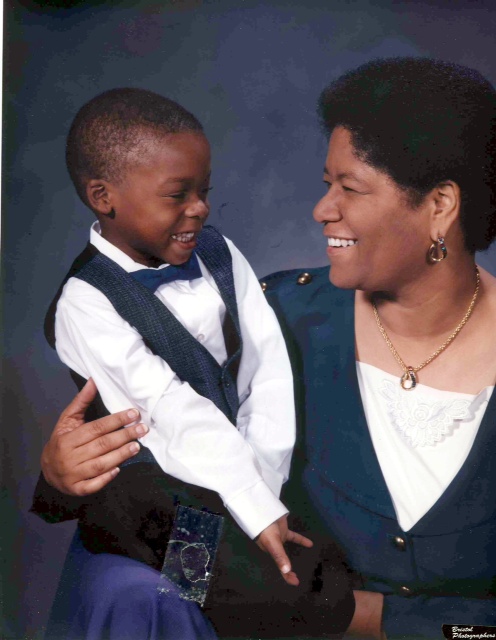

(Photo Courtesy of Claire Smith)

I didn’t know right away what I wanted to do. By the time I got to college, I was kind of lost. I wanted to be a lawyer. I thought lawyers were what you see in the movies. The courses were just deadly dull though.

So, I stayed about three years at Penn State because I was forcing myself to do something that I thought would be interesting, but it certainly wasn’t anything that I loved. I was at a university with 30,000 people, and I just felt invisible. So, I left after three years, and I started working full time in the department stores.

My dad got frustrated with me, and he finally said ‘What do you want to do?’ I said that I wanted to work for a baseball team. He said, ‘Well go do it. Go back to school and get the degree that you need to get.’

So, I looked in the immediate area, and Temple University had a Public Relations degree. So, I went there, and to get that degree, you had to take a journalism course. So I took a course taught by Jacqueline Stenk, and I think I was hooked three minutes into the class.

A light bulb went off, and I was just like, ‘This is what I want to do. Forget public relations, I want to write about baseball. I want to be a baseball reporter.’ And from that time on, that was my goal. I headed to newspapers, started freelancing at the Northwest Suburban, the Bucks County Courier Times in Pennsylvania, and covering concerts, but knowing that the prize was to become a baseball writer.

We had a rather archaic, small-minded sports editor, who pretty much had never had a woman on the staff, so I credit him for making me move away from my family and outside of my comfort zone for the first time.

We had a rather archaic, small-minded sports editor, who pretty much had never had a woman on the staff, so I credit him for making me move away from my family and outside of my comfort zone for the first time.

The Philadelphia Bulletin was the best journalism school I ever attended. I worked with the likes of Bob Wright, Jim Barniak, Richie Ashburn. I got to edit Richie’s copy. It was great.

I started out on the news side as a news editor, and then I received an offer to become a high school sports writer at Newsday in Long Island. I accepted because this was my dream.

I went to talk to my editor at the Bulletin to notify him, and he said ‘You’re not even going to give a us chance?’ So, I said, ‘Well, it’s sports; it’s what I want to do.’ He replied, ‘OK, well let me see what I can do.’ Within a week, I was news editing in sports with a promise of writing soon to come. And it did.

I covered college basketball and college football, all very great learning experiences. We had a lot of other baseball writers, so I knew that there wasn’t a chance to do that, but I was covering sports under a wonderful editor named Bob Wright.

Baseball went on strike in 1981, and it went on for a while. And the day that it came back was the day that Pete Rose broke Stan Musial’s National League hit record. Stan was in the park, there was a big crowd, half of them booing, half of them cheering. So, my boss asked me to go the park and write sidebars as my first major league assignment. I loved it.

A year later, the paper folded, and there was a giant job fair in our offices because editors came from around the country looking to hire. The sports editor of the Courant, Jim Smith, came.

They were going from a city paper to a regional paper, and they were about to establish something pretty unprecedented in sports coverage. They were situated in Hartford where they had a National Hockey League team, but the paper was going to go into Boston and cover the Celtics, cover the Red Sox, cover the Patriots, as well as go into New York and cover the Yankees, Mets and the Giants. It was pretty amazing. He was looking for sports reporters to do those things. He was looking for two baseball writers, and he hired me.

So, I got my first full-time baseball job, and I covered the New York Mets. It took the paper about a month to say, ‘What are we doing? There’s only one paper in America that covers three major league teams, and that’s the Los Angeles Times. We aren’t the L.A. Times.’

So, they dropped the third most popular team, which was the Mets. I lost my beat.

Shortly after that though, the Yankees beat writer, Clemson Smith, wrecked his knee, ended up on crutches, so they told me to go cover the Yankees until he comes back. So I did and it was the summer of ’82.

Three managers, six pitching coaches, and 54 player changes. It was a typical George Steinbrenner mess. A train wreck. I covered it, and it was an absolute blast.

By the time Clemson’s knee healed, our managing editor told the sports editor, ‘If you take Claire off the beat, you’re fired.’ So, Clemson got the newly-created Celtics beat and moved to Boston, and I got to New York. I ended up covering the Yankees for eight years.

After that, I spent about three years as a national baseball writer, assisting the sports editor, just going around the country and covering the big stories. In 1990, I received and accepted an offer from The New York Times to be a national baseball writer, I stayed eight years.

(Photo Courtesy of Claire Smith)

I had a son, two elderly parents, and I had to get to a place that was more regional coverage and less national, so the travel was less demanding.

I went back home and took a job as a columnist at the Philadelphia Inquirer, staying there for eight years.

That’s when n newspapers were really starting to cycle down. I made it through the first couple buyouts and the first round of layoffs, but I honestly didn’t think I’d make it because it seemed to be about age and salary. About that time, ESPN was establishing itself in the vast television world, and we had a little sector of newspaper expatriates, known as the news editors. I joined up.

We had a very dynamic leader in our department named Norby Williamson, who hated the fact that ESPN might be accused of being the toy store or the candy store and not knowing anything or caring at all about the news. He wanted to erase that image, so he brought in sports newspaper people. His mission was to hire sport-specific news editors. He brought in ex-sports editors, columnists, and veteran writers such as myself.

So I was brought in as the baseball editor to work with Monday Night, Sunday Night, and Wednesday Night Baseball telecasts. My job was to travel with the talent, deal with the hard news, and persuade them to deal with the hard news when they were uncomfortable with it.

I work with the ex-athletes who don’t know a thing about journalism, but are very hungry to learn and hungry to do it right. They don’t want to look stupid; they don’t want to have to issue apologies for saying things that they shouldn’t have said. They have since expanded the position, where my news editing skills are now also used on Baseball Tonight.

So during the season it’s really a job that is six days a week, and it just goes non-stop from February to October.

In 1984, American League President Lee MacPhail had long since dispatched of any issue of women in the clubhouse by making the decision to allow you in if you had the credentials.

The NL president did not do the same, so you always knew where the accepting teams were, and where the trouble spots were. The trouble spots were Montreal, Cincinnati, San Diego, and depending on who the manager was, Atlanta. There were issues with Dale Murphy.

In ’84, that was going to be my second year covering the postseason, we could see that San Diego was going to make it. So, my editor, Jon Pessah, wrote to the NL saying that he was worried about sending me to San Diego.

We got a letter back from the league telling us not to worry because the postseason didn’t belong to the teams, it belonged to the League, and then the World Series belonged to the Commissioner’s Office.

So the Padres get into the playoffs and are set to play the Cubs. The series starts in Chicago, the Padres win the first game, and I go in to do my job.

I was immediately thrown out of the Padres locker room, to the point where one of the Padre employees put his hands on me and pushed me through the door.

I was immediately thrown out of the Padres locker room, to the point where one of the Padre employees put his hands on me and pushed me through the door.

As I was being thrown out, by what I considered to be physically abusive behavior, I said I was told that I had permission to be in here, and Padres General Manager Jack McKeon, he was a gentleman, shrugged and said, ‘It’s Dick Williams’ clubhouse.’

There was a lot of verbal abuse, from a certain group of players on the team. Usually, when you encounter a situation like that, as much support as you get from your peers after the fact, they have to do their jobs as well. Nobody holds everyone up and says, ‘Wait, stop.’ People have to do their job, and I had to do mine, but I wasn’t being allowed to do it.

As I remember being pushed through the door, here comes manager Dick Williams into the news conference area. I went up to him and said, ‘I was told that I had permission to be here, and Jack McKeon said that this is your clubhouse, so…’ and he said, ‘That’s right,’ and just kept walking.

So, I’m standing outside the door, I have a game story to write about the winning team, and I have nothing from them. Just then, my friend, fellow Yankee writer, Henry Hecht comes barreling down from the pressroom and he immediately knows what’s going on.

He said, ‘Well, what do you need?’ I told him that I needed quotes. He asked me what I wanted him to do, and I asked him to go get Steve Garvey. We had already become friends, exchanging letters in my college years.

So, Henry went in, and he later told me that reporters surrounded Steve. Henry made his way through, told him that I had gotten thrown out, and Steve immediately came out and spoke to me.

I got emotional, and I started to break down a little, but he told me that he would stay there for as long as I needed him. He said that I have a job to do, and that he wanted me to get it done. So, I did my job, and he gave me what I needed.

The whole situation was very traumatic. By the time I went to go see the Cubs, word got out of what had happened.

I knew a bunch of Cubs just as I knew a bunch of Padres because everybody plays for the Yankees at some point. Goose Gossage, George Frazier, Don Zimmer — and they were outraged.

They said, ‘This is our ballpark, this doesn’t happen in our ballpark.’

By the next day, it turned into far too big a story, and the media was pretty biased against the Padres.

They had some vicious players who were apart of the John Birch Society. In my childhood, this group was pretty much known as the political version of the Ku Klux Klan. So these guys made it a point to be very vocal about being Birchers, and it made people in baseball very uncomfortable. And then when this happened, not even just that it happened, but because it happened to an African-American woman, it kind of, to use today’s phrase, “went viral.”

It became a huge news story in literally Peter Ueberroth’s first week as the new commissioner of baseball. He didn’t know that there were different rules in both leagues, so before game two in Chicago, he unilaterally opened clubhouses to anyone who had credentials. He said, ‘It’s my sport, not your sport.’

Before that game, I was standing by the Cubs’ dugout on the third base side because I felt a lot safer there. Then, before I knew it, I saw Goose running right at me, and he said, ‘You’re in there tonight! Why didn’t you come get me? You’re definitely in there tonight!’ There was steam coming out of his ears, he was so angry at the situation. So, I told him, ‘This is why I didn’t come get you, I knew exactly what you would do! I didn’t want to cause a scene.’ I knew that if he had known what happened, there would be a couple dead people lying around. He’s the biggest guy I have ever covered in baseball.

Those are the folks that I want to remember the most: Goose, Garvey, the Cubs, the Yankees, who filed an amazing protest against what the Padres did. When I asked the Yankees’ media director why they were doing it, he said, ‘Because no one treats Yankees beat writers like that.’ I remember going, ‘That is so cool!’ Everyone was coming to the defense of the female reporter, and the Yankees were coming to the defense of one of their people. I’ll never forget that.

The whole thing was very difficult. Ask anyone who goes through something like that, it just traumatizes you. But, what happened to me was mild compared to some of the stuff that other women have had to deal with.

I’ve never had a live rat sent to me in the form of a present in the press box. I’ve never had a player charge at me to the point where his teammates had to hold him back and say that he needed to kill them if he wanted to get to me.

Some of the things that have happened to other women are terrifying. We had to deal with ignorance, we had to deal with some of the things that players of color, or players from Latin America, from 20 or 30 years before, had to deal with. It was a different level of prejudice and bullying. You found pockets of support that were surprising sometimes.

I always thought my best sources, almost to the point of being my big brothers and watching my back, were the African-American players, Don Baylor, Dave Winfield, Willie Randolph, and as Reggie Jackson used to call it, ‘The richest ghetto in America,’ because the Yankees had a segregated clubhouse, it was unbelievable, so it probably was the richest ghetto in America.

I always thought it was a black thing, until I spoke to other women, and it was quite obvious that it was the same for all the women that they found their biggest support among African American players as well.

I always thought it was a black thing, until I spoke to other women, and it was quite obvious that it was the same for all the women that they found their biggest support among African American players as well.

Hall of Fame safety for the San Francisco 49ers’ Ronnie Lott was at one of the first AWSM Conventions as a guest speaker, and someone actually asked him the question, ‘Why is it that women have found the most support from African-American players?’ And Ronnie said, ‘I guess it’s because we know what it’s like to walk into a room and be instantly hated.’

And everyone thought that it made sense. I remember Ken Griffey Sr., the original, the best, chastising a teammate for cursing in front of me. I said ‘Ken, it’s OK. I adopted the Umpire Rule, which is as long as you don’t use the word ‘you,’ I don’t take it personally. It’s your clubhouse; it’s your language. I’m not here to change you.’ He said, ‘No, it’s not right. While I’m here, no one is going to do that in front of a black woman. I’m just not going to have it.’

One of the funnier incidents was in 1987 when the Hartford Courant decided to make our special section coming out of spring training about African-American players. One of the themes was that once African-Americans knew that their playing careers were over, their baseball careers were over because they couldn’t get coaching jobs that would lead to managerial jobs. This section led to a new dialogue on baseball’s hiring policy. The hiring story became huge, and it sparked a kind of nonviolent revolt in baseball.

I was a Yankee writer; we opened on the road that year in Kansas City. I was walking onto the field, and Dave Winfield was out there stretching, and he said, ‘Claire, Claire, come here.’ Dave is a riot, a real great guy. So he says, ‘Some of the brothers were talking, and we starting talking about you and we noticed not only are you a woman, but you’re BLACK! So, we decided, whatever you need, you just come to us.’ I said that I would. He unintentionally makes me laugh all the time.

People ask me all the time, ‘What was the hardest thing to overcome, being a woman, being black,’ and I said it’s no contest because it’s unacceptable to be a racist, but it’s still very acceptable to be an idiot when it comes to gender. And that’s been proven over and over and over again. I could never imagine someone dropping the n-word in a clubhouse then. There would have been hell to pay. But, some of the stuff that comes out of player’s mouths that are aimed at women, it’s just juvenile. And it still happens today.

People ask me all the time, ‘What was the hardest thing to overcome, being a woman, being black,’ and I said it’s no contest because it’s unacceptable to be a racist, but it’s still very acceptable to be an idiot when it comes to gender.

The Baseball Hall of Fame project (I worked on) meant the world to me because it gave me some of the most lasting memories of my entire life. It was the Oral History Project.

The commissioner at the time, Fay Vincent, found out that nowhere in baseball was there a video history of some of the great contributors of the game. So, he funded this project with a couple of his friends, to basically go and have the iconic figures in baseball tell us their life stories in three-hour increments.

We just went around the country for about five or six years grabbing up as many Hall of Famers, Negro League players, umpires, executives, what have you, and just opening up a camera lens and a microphone and asked them, ‘When is the first time someone put a baseball in your hands?’ And they walk us through their lives. I got to meet some amazing, amazing people who had some awesome stories. I learned so much about baseball.

Some of them were clinics; where just sat back and just listened to baseball stories, or sometimes we would get to listen to someone like Yogi Berra who was on the front lines of World War II.

Yogi also talked about how he grew up also playing softball, and he talked about how much it helped.

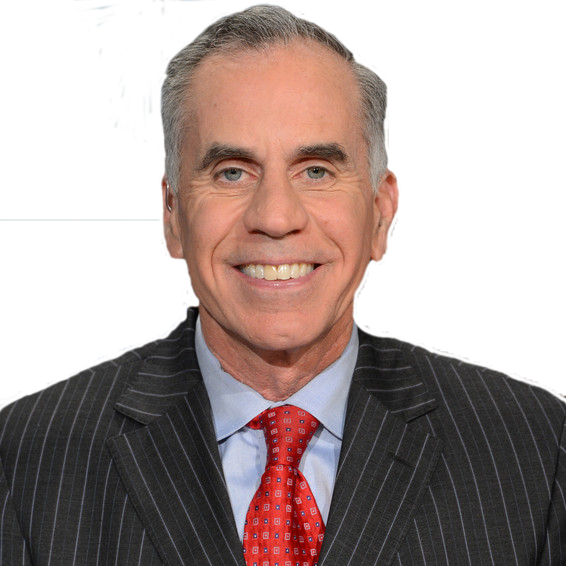

Claire Smith accepting the Sam Lacy-Wendell Smith award in 2013.

(Photo Credit: Dave Ottalini)

We talked to Monte Irvin, who was the first player that baseball approached to break the color barrier. Sitting there, you could hear a pin drop because Monte said that he had been so scarred by World War II, not the war, but his treatment as an African-American in the army, that he basically had a breakdown when he came back. He told baseball that he could not handle being the first black player. And that’s when they went to Jackie.

Willie Stargell, first African American in the Texas League. He was from California, he had no idea what happened in the South. He said that he was basically told that he would either be shot or lynched. He played a game in Texas, and afterward his car backfired. He told me, ‘Claire, I just lost my water.’ He just knew that somebody had shot at him.

But there are stories of triumph too. The Dodgers, tired from the segregation that they faced in Florida with Jackie and Roy Campanella, moved the team from Cuba to a self-contained town: Dodgertown. It had its own movie theater, its own laundromat.

The Cardinals did the same thing in St. Petersburg. They bought a roadside motel and transformed it into living quarters. Bob Gibson and Bill White told me stories about the entire team. They had a swimming pool, barbeques. It was a fully integrated team. The motel was close to the highway, so Floridians would drive their cars up to the building, and watch what was going on with this team. It was like watching a movie for them; they’d never seen this before. That was in our lifetime!

Part of the oral history project was to tour with Larry Doby, Joe Black, Fay Vincent and others, and we just went to college campuses.

To watch Larry kind of whimsically smile as college students would ask him why he just didn’t refuse to get out of the front seat of the bus. Larry would just very patiently explain that it was the law of the land back then.

We’ve been through a lot, but we have come a long way. I didn’t experience what my parents did, and they didn’t experience what their parents did. And god knows that my grandmother didn’t experience what her father did because he was a slave.

It is amazing to walk into any event and be very comforted by the fact that you’re not alone. You could go on the road for weeks and not see another woman. Between the two coasts in middle America, it could be very lonely. But now, it seems like we are one of the guys.

A lot of women are on television, or they are sideline reporters. It’s pretty cool. Working at ESPN is amazing. They are so proud of their record with diversity. I see it and I appreciate it.

I don’t know if women gravitate to certain sports. I don’t know of any female NFL beat writers, but I’m sure that they are out there. Hockey and basketball always are easier because they were sports that usually had to beg for coverage, so they gave women more access. I would say that there is still more work to be done, but I definitely cannot look around a room and say, ‘Where are the women?’ That’s not the case anymore. It’s different.

The dwindling newspaper base versus the ever-growing Internet platforms. … It’s not the same as it was five years ago. Today, you have to try to always keep up with what’s going on, and also look ahead. Do what racecar drivers do, which is try to envision what is around the next corner.

ESPN is constantly asking new people for ideas. They are always trying to think outside of the box. Be patient, but always remember the basics of the basics: Accuracy, integrity, and honesty. Treat everyone professionally and how you would want to be treated.

Don’t cut corners, and don’t give in to conformity. Be different. If you are on a beat, and there are ten reporters on the beat, and nine of them follow each other around, don’t be the tenth.

Blaze your own trail. If someone starts following you, don’t let him or her gain insight into what you are doing. If you’re talking to Alex Rodriguez, and I come up, stop asking questions. Demand that I ask a question, and if I don’t have one, tell me that it’s your interview. This goes for pregame though. After the game, it’s everyone for themselves. Protect your sources, but demand that your sources protect you by having as much integrity as you do.

…It’s not an expedient world. You have to have patience. Someone will ask you one day how you got there, and if you’re an overnight success, you have to just smile. You don’t have a story.

Back in my day, everyone wanted to start at The New York Times. Now I imagine it’s ESPN, Comcast, or Fox. Be willing to explore all the 50 states. Not everyone starts as star. Again, it’s not an expedient world. You have to have patience. Someone will ask you one day how you got there, and if you’re an overnight success, you have to just smile. You don’t have a story.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski Adam Schefter

Adam Schefter Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor Frank Deford

Frank Deford Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Bryan Curtis

Bryan Curtis Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga