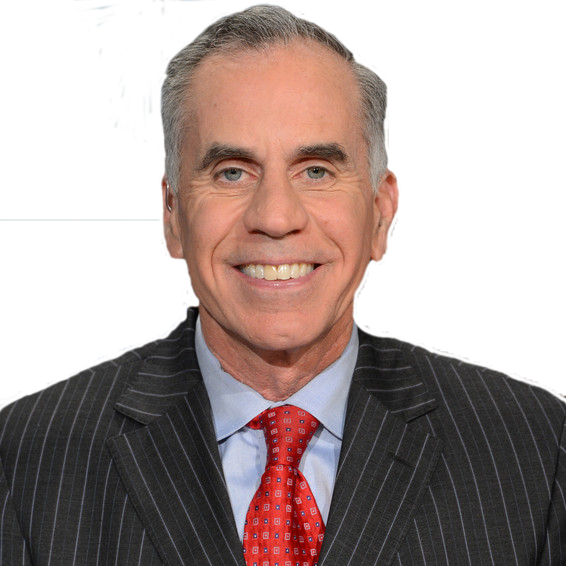

TIM KURKJIAN

Biography

Kurkjian grew up in Bethesda, Maryland and enrolled at the University of Maryland in the fall of 1974 and received his bachelor’s degree in journalism in the spring of 1978 from the Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

Immediately after graduating, Kurkjian took a position at The Washington Star. In his time at The Star, he had a multitude of responsibilities: answering phone calls, writing high school sports briefs, running errands for seasoned reporters. Kurkjian eventually became a staff writer for The Star in 1981, but that role was short-lived, as the newspaper went out of business that same year. After stints with Baltimore News-American and The Dallas Morning News, Kurkjian worked for the Baltimore Sun covering the Orioles.

In 1998, Kurkjian joined ESPN as a baseball insider and has held that position ever since. Kurkjian has covered every MLB All-Star Game and World Series since 1982 and has published two books, America’s Game and Is This A Great Game, Or What?, with a third book in the final stages of publication.

Interviewed by Jimmy Reed

I grew up in a baseball house.

My father, Jeff, was a really good baseball player. My two brothers, Matt and Andy, are in the Catholic University Baseball Hall of Fame. In [Walter-Johnson] high school, I played baseball and basketball. I grew up loving all things sports, but baseball was really the only language spoken in my house. It’s what we talked about and thought about.

I knew at a very young age I had to make a career out of my love for sports. It was really the only thing I had. I wasn’t a particularly well-rounded kid. I didn’t have a great deal of interest in other things, not a whole lot of hobbies. I played sports all day, and when I wasn’t playing them, I was reading about them.

I really don’t recommend anyone being as narrow-minded as I was, but that’s what I loved.

When I was in high school, my basketball coach told me I should try writing for the school paper. I gave the paper a try and I was really bad at it. And I’m not exaggerating ... I was really bad at it. But I enjoyed doing it and I did it for a couple years.

My second year, I was the sports editor, and it just seemed like that was going to be my best chance to stay in sports somehow. I graduated from high school at 5-foot-3 so I knew my playing career wasn’t going anywhere professionally.

I went to the University of Maryland, majored in journalism. I wrote about sports for all my papers. One of my English teachers finally asked me, “Can you write about anything else, or is this it?” I essentially said, “Well, this is it.”

I did cover the Rockville City Council for one semester for one of my journalism classes and that was pretty dull. I got through it, but I didn’t write very well about it because I didn’t have any interest in it. I figured, “Once I learn to write, I’ll write better when I’m really interested in the topic.”

I eventually figured out how to write with a lot of help from a lot of people, but mostly by writing a lot.

I wrote for my local paper, the Montgomery Journal, while at Maryland. I really enjoyed it because I got to cover high school sports, and I’d go to the gyms I used to play in while I was in high school. So I didn’t write for my school paper, The Diamondback, but for my local paper.

When I got out of college I went to the Washington Star and basically begged my way into the door. Once I got in, I said, “If this is what I want to do, I want to do it here.” It’s a local paper; it’s a great paper; it’s got a great sports section.

So I just kept showing up every day doing whatever they asked me to do. I delivered coffee to all the writers. I made runs to McDonald’s and to Roy Rogers in the middle of the night. I did a lot of stuff, and the whole time they were giving me a chance to write, and I would take scores over the phone. I would write up the one-paragraph blurbs from high school games and I thoroughly enjoyed that.

I thought it was the coolest thing in the world. The day Art Monk was drafted by the Redskins, years before the Internet and cellphones, every person on Earth was calling The Star asking, “Who’d the Redskins draft?” And I was the guy in there who had just got the information off the teletype or whatever it was called and I would tell them, “The Redskins got Art Monk.” I felt like I was at the center of the sports universe. I had all of the sports world right there at the palm of my hand.

I learned how to be a newspaper guy by watching all the other newspaper guys work. I can’t tell you how many times I said, “Wow. That’s how you do that, eh?” Working at The Star was the greatest learning experience I ever had.

I spent over two years freelancing there, but wasn’t an official staff writer until January of 1981. The Star folded in August of 1981, so I had to go get another job. That was easily the most disappointing day of my professional career.

I lost two jobs in two months. The L.A. Times even called me, not to offer me a job, but because they noticed that I had lost two jobs in two months and I was a piece in their story on the death of the newspaper business. I said something really stupid like, “If I lose another job, I’m going to join the circus.” That ran on the front page of The Times.

My boss from The Star had already become the sports editor for the Dallas Morning News, so when he found out I lost another job, he offered me a job there. I was covering all sports.

I’ll never forget my first day there. I walked in the office and here I was … this tiny little kid from Maryland walking into this big office in Dallas.

Harless Wade, a prominent writer at the time, saw me walking through the office and he looked at me and said, “You must be the new guy.”

I said, “Yeah, I am.”

He said, “You have to be the smallest damn Yankee I’ve ever seen.”

So I was immediately identified not just as really short, but also as a Yankee, too.

I was at the Dallas Morning News from December of 1981 through the 1985 Texas Rangers season. I had a great time in Dallas. I learned an awful lot. The way I got the baseball beat job was that Skip Bayless, the Skip Bayless, was the lead columnist at our paper, and he got an offer to go to the other paper in town. When he left, Randy Galloway, the baseball writer at the time, became the columnist, and with about two weeks before spring training, my boss told me I wasn’t ready, but I was now the baseball writer.

I had covered minor-league baseball in 1979 at The Star. But this was the first year in 1982 that I was the full-time beat guy for a major-league team. It was great. I didn’t understand how the beat worked. All I knew was that I loved baseball and loved going to the games. I didn’t understand the competition of the beat, and I got my brains beat out for a year by the other writers on the beat. But I learned from it, and I came back in 1983 and started to hold my own.

After the Rangers 1985 season, I moved to The Baltimore Sun to cover the Baltimore Orioles. That was great because I came back home, and that’s where I wanted to get to.

More importantly, I wanted to cover a team that people were truly interested in, and that was the Orioles. Keep in mind, there was no Ravens team then. It was just the Orioles. So The Sun really valued my writing because the Orioles were the only game in town.

I covered the team for four years, 1986 through the 1989 season. The team was really bad for the most part while I was there. In 1988, the team lost their first 21 games of the season, by far the worst start in baseball history. In 1989, the team recovered unbelievably and almost made the playoffs. This was by far the most exciting year for me on the beat.

After the 1989 season, Sports Illustrated called me and offered me a job as one of the baseball writers there. I took that and stayed there for eight years.

Eight years at SI, and then [at] the start of the 1998 season until today I’ve been at ESPN.

The steroid story in baseball has probably been the most impactful story I’ve covered because it has gone on for such a long time. It covers so much ground and involves so many people. It has in many ways made all our lives a lot harder and more complicated because of the nature of the controversy.

I’ve probably written more words regarding the steroid era than any other topic for the last 15 years or so. It's been hard because I don’t enjoy it, but it is an important story, so I have done the best I can with it. There’s still so much that we don’t know.

I’ve covered every World Series since the beginning of the 1982 season. I’ve never missed a World Series game, starting with Game One of the 1982 series.

I’ve written two books and I’m just finishing a third. I wrote America’s Game in 1997 and wrote Is This a Great Game, or What? in 2007, and I’m just finishing my third book any day now. It’ll be out in January of 2016. As of right now, it’s titled I’m Fascinated by Sacrifice Flies.

For the first book, the publishing house called me and said, ‘We want you to write a book and here’s how we want you to do it.’ It was a lot of fun, and I did it in conjunction with the Hall of Fame.

My second book was all about my favorite stories from my first 25 years covering the game. That was all about the writing for me. That was the single-most satisfying professional part of my life: publishing a book that was in my words, was my story. My next book is going to be similar in tone and volume.

Transitioning from writing to broadcast was difficult at first. I spent a fortune on clothes. I wear more makeup than my wife. I spend a lot of time walking around talking to myself. I finally figured out in a short amount of time that broadcast is just like presenting a story in the newspaper, but you just have to present it in another way.

The newspaper business and magazine business taught me how to tell a story. Being a reporter, I knew how to report the story; I just had to do it in a slightly different way for television. The newspaper training I got trained me to be on TV, and I’m sure it could work the other way, but I think it’s a whole lot easier to go in the other direction, the way I did it.

I’ll always love writing the most. But I must say, I love doing television because I can talk about something right now. With the newspaper, I’d have to wait ’til the next morning. With the magazine, I’d have to wait an entire week. Now, if I need to say something, I can say it now and not have to wait. The spontaneity of TV I really like.

My favorite story that I’ve ever covered was Cal Ripken’s chase of 2,131 consecutive games played. It was an entire combination of stories, but the night that Ripken broke the record, it was the greatest night that I’ve ever spent in a major league park. It was so much more than baseball. It was about neighborhoods, family, commitment and showing up every day and doing your job. I saw people crying in the crowd.

I had a Toronto writer come up to me before the game. He hadn’t really covered the chase at all. He showed up that night and he said, “Tim, I don’t see it. I don’t get it. I don’t feel it.”

I said, “Let’s see what happens. Check back with me after the game becomes official and let’s see what happens.”

After the game became official in the bottom of the fifth and Ripken made that unbelievable, impromptu 22-minute run around the park, my Toronto writer friend came back to me with tears in his eyes and said, “Ok, I get it.”

Everyone in the ballpark that night got it. When you’re moved to tears at a major league ballpark, that tells me how great a story that is.

To be successful in this industry, you’ve got to do three things. You’ve got to show up every day. You’ve got to be prepared. And you’ve really got to try.

If you’re doing all those, you’re going to be fine, no matter what. But you have to be curious. You have to come to the ballpark as a beat guy and look for players and make sure they’re all there. You have to ask yourself, “Is anyone not here today?” If so, I’ve got to find out why.

When a play happens, or when something happens it the game that you don’t understand, you’ve got to go to the guy who made the play and say, “Here’s what I saw. Did I see it right?”

I think that curiosity is an extremely important part of being a journalist, reporter, writer. It’s about asking the questions.

When is the last time that happened? How did that happen? Why did that happen? What is the story here?

Those are the questions that you have to ask yourself every day to do the job, and it’s crucial to what we do.

Jimmy Reed, a 2013 graduate of the University of Maryland's Philip Merrill College of Journalism, is a pitcher for the Palm Beach Cardinals in the Florida State League. A former pitcher for the Maryland Terrapins and author of a number of journals for this web site, this is his third year in professional baseball.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski Adam Schefter

Adam Schefter Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor Frank Deford

Frank Deford Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Bryan Curtis

Bryan Curtis Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga