Neil Leifer

Biography

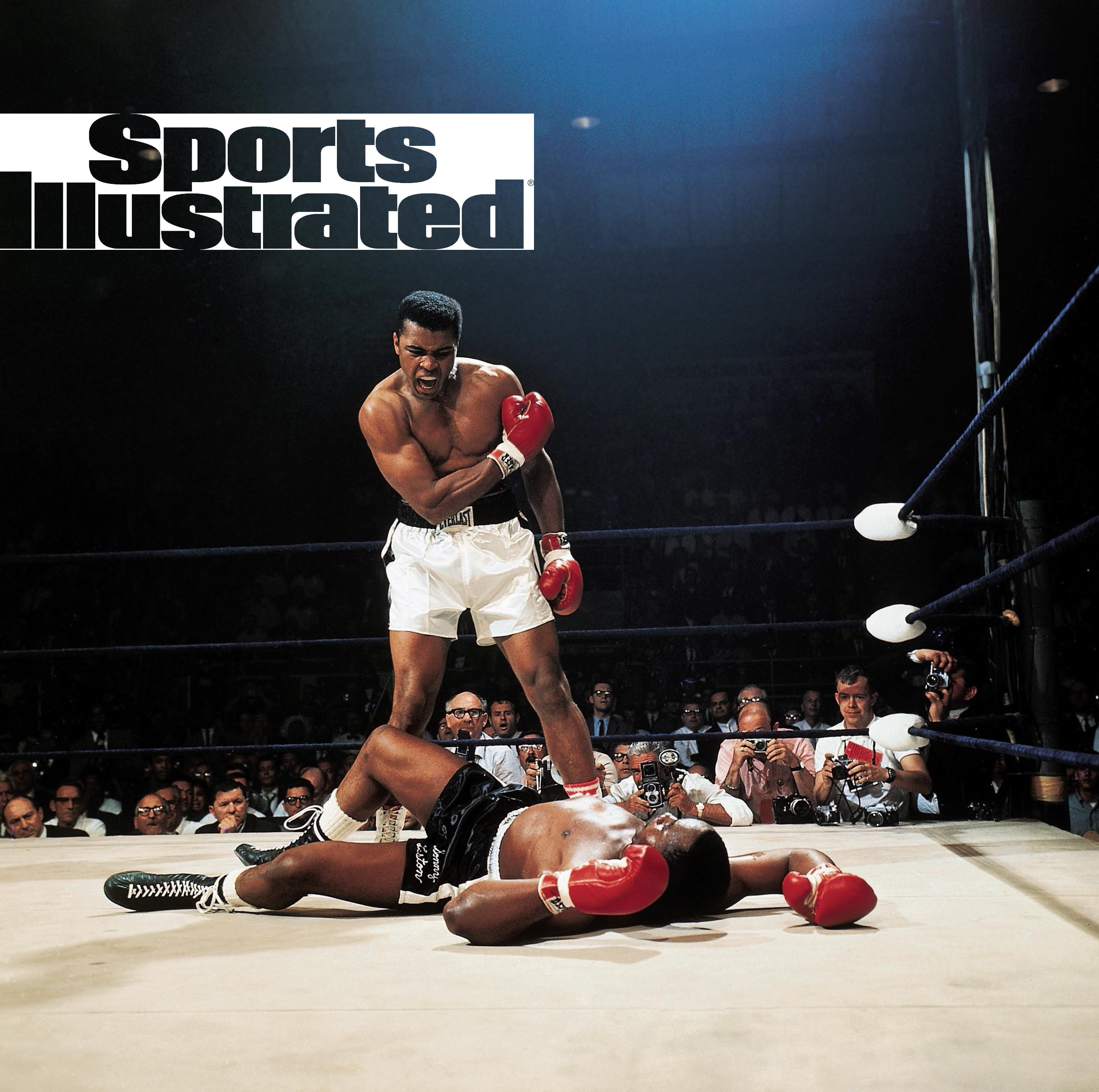

Neil Leifer worked as a professional photographer for 50 years, working for magazines such as Sports Illustrated, Time and LIFE. He photographed 16 Olympics, four FIFA World Cups, 12 Super Bowls and manyWorld Series. He photographed his favorite subject, Muhammad Ali, on almost 60 different occasions. His work has been published in numerous books and on display in numerous museums, including the Newseum in Washington, D.C.

Interviewed by Samantha Medney

Istarted taking pictures as a kid, 12-or 13-years-old, as a boy in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

I belonged to a settlement house. The Henry Street Settlement House. One of those places designed to help keep kids off the street at night to stay out of trouble. Not that I was a likely gang member or drug user, that certainly wasn’t very likely, but this was a tough neighborhood. A poor neighborhood - and there were drugs and there were obviously kids getting into trouble in terms of gang membership.

The settlement house was a place kids could go at night; there was a gym and you could play some sports, which was my first love.

There were places one could learn to play an instrument, music, dance, sewing classes -girls in those days gravitated to that kind of class - and there was a photo group.

So often a teacher could be so important to one’s life. We had a woman named Nelly. She had an unpronounceable Polish last name; I certainly can’t spell it, so let’s just say Nelly.

Nelly taught this group and it was a two night-a-week class. Where you’d come in, let’s say your nights were Tuesday and Thursday (it could have been Monday and Wednesday), and by the way, kids in the Lower East Side couldn’t afford cameras or film, but the settlement house had donated cameras. They were an American company called Dejur. These were little Instamatics; they would give you a camera and a roll of film. The film was donated by Kodak. Life Magazine’s photo lab used to donate film to the settlement house and you would go out on the weekend and shoot a roll of film.

If your days were Tuesday and Thursday, on Tuesday, Nelly would teach you and supervise as you learned how to develop your film into a roll of negatives. Obviously this was all black and white way back then. On Thursday you printed the best of your one or two pictures into an 8x10 print with Nelly looking over your shoulder and teaching you how to do darkroom work. It was a fun group. Usually there were about six or eight [kids] each of the nights.

Our little group ended up producing three Sports Illustrated staff photographers. John Iacono has been a life-long friend of mine, Manny Millan a former Sports Illustrated staff photographer who started off at the settlement house, and one guy - Stanley Kubrick- who started at Look magazine, which was a very prestigious magazine to work for. Kubrick had been a Look magazine photographer. It was a very fun thing to do and you might say that I got the bug. I really enjoyed it.

The odd thing is I wasn’t a very good photographer back then, and I was a terrible darkroom technician. I loved working in the darkroom. I really didn’t have the touch. I really didn’t have the patience to be good in the darkroom, but I enjoyed it.

When I wasn’t going to the settlement house, I worked in all sorts of jobs growing up. I actually used to shine shoes when I was 13 or 14-years-old. Then I got a job delivering sandwiches in New York and I got enough money to buy some film and get some really inexpensive cameras. I think I had a Brownie Hawkeye as a kid and that’s how I started.

•••

On the digital age…

It hasn’t really affected me at all because I’m no longer taking pictures; I’m a filmmaker now. The rare times I do shoot pictures - professionally - I usually have someone who’s really good with the digital cameras. I’m somewhat of a computer illiterate. Sending text-messages was my big learning thing for me in 2013.

My grandkids were making fun of me because I didn’t know how to text. I mastered texting. I know how to send and receive emails, but I’m not very comfortable with the digital because I’m just not computer-literate enough.

There are so many different possibilities. Just with setting the camera up. I shoot digital. I shoot for fun, I shoot my grandkids, I shoot my girlfriend. I shoot pictures when we’re on vacation and I enjoy doing that, but I’d be hard pressed to go out and do what I did so many years at Sports Illustrated and Time magazine to feel comfortable because I don’t know the equipment well enough.

Having said that, I think the cameras are fantastic. The cameras today are so much better. The lenses are better; they’re lighter, they’re faster, they’re sharper. The whole digital thing is a good thing for photography.

What fascinates me is if I were to shoot professionally today, I would have to master the digital side of digital cameras. What is interesting is the photographers who are shooting, so many of the best ones are the same photographers, who were so good way back when there was a thing called film that you actually had to put in the camera.

Annie Leibovitz: great photographer when she was shooting film and she’s pretty damn good shooting digital. So many of them - Jim Nachtwey, Walter Young, Steve McCurry, Harry Benson - so many photographers who I respect and admire, have made the transition seamlessly.

So it really is the photographer, not the camera. It’s just the equipment is so much better. Of course there are so many young photographers who would probably have been brilliant photographers in the age when one used film.

•••

Ninety percent of the assignments I did, you’re shipping your film out and the magazine is published when you’re still shooting out on the field. Certainly during an Olympics, even something like a championship fight or a Super Bowl, you’re sending film back, which is being processed many, many miles away from where you’re shooting and printed in the magazine before you make it home.

I’ve not had any reason to do darkroom work. I don’t even know what today’s enlargers would look like. I don’t know anyone shooting film and right now you don’t need a darkroom. I’m not computer-literate enough to do Photoshop, but I don’t really like it anyways. I like taking photos and having the picture published the way I took it, not the way it’s been fixed.

I haven’t really had to deal with it in my case. I’m old school. I like taking pictures. I like taking good pictures that don’t need to be fixed. You don’t have to eliminate anything or add things to it. Having said that, there is a certain misunderstanding that the old days when we didn’t have such a thing as Photoshop or anything that a talented darkroom technician could take a negative and enhance it - not change it.

I’m a huge fan of Ansel Adams and Yousuf Karsh’s work. You look at their black and white photos and you don’t think that you just slap that negative in an enlarger and the prints come out the way they look. You dodge it and burn it here and make the sky a little darker.

It’s not a whole lot different than what one does with Photoshop as long as you’re getting the best out of the negative, sometimes getting the latitude out of the negative simply means you expose some for shadow area - the sky for example might need a little bit of burning so it comes out the way it actually looks. It isn’t doing anything to change the picture.

The film itself can’t record the way your eye sees it and the way you took the picture. I’m certainly opposed to changing things, to adding to my picture, fixing it as I like to say.

I’ve never been personally involved in the ethical end of it. When you’re shooting for the cover for a magazine, for example, it was not unusual in the days I was shooting, let’s assume they needed to darken the sky to hold the logo because the logo would have clashed or maybe not jump out of the top part of the frame where the logo was.

I never had anything wrong with that. There’s a reason it’s done, which is nothing different than a darkroom technician burning in the sky, which I can promise you was done with LIFE magazine during the heyday of photojournalism.

•••

I grew up in Lower East Side in a low-income housing project. My dad was a postal employee, my mother was a corsetiere, my brother Howie is five years younger than I am and we had a pretty nice childhood.

It’s interesting - I don’t know how much of my energy and my sort of go-get ’em attitude comes from growing up the way I did, but I’d like to think it was always a benefit. I was a good student and sort of never understood why my parents thought they had a young doctor on their hands. At a certain point I lost interest really in school. I was a very good student, mainly it was because I found something I enjoyed doing better and it was photography.

The idea of being sports photographer occurred to me because I was a rabid sports fan. The idea that someone would pay me to go to the World Series, or a championship fight or the championship football game - before there the Super Bowl, just made me pinch myself.

They’re kidding. They’re paying me to do something I enjoy doing, giving me the best seat in the house. It was fun and I really had a good time and I was very lucky.

Time went on and there was a whole world out there that I wanted to explore. I pretty much left sports photography in 1978. I moved from Sports Illustrated to Time magazine because I wanted to cover other things. I’d like to say I covered everything from Charles Manson to the Pope.

I got to cover the White House, the animals in Africa, and the Superpower aircraft carrier in the United States Navy. I flew with Top Gun, I did a lot of things, kind of Walter Mitty. I lived out a fantasy and I’d like to think the camera was my ticket to the whole world. Places I never imagined I would get to see or explore and I did get to see these things because of photography.

•••

My career pretty much paralleled Muhammad Ali’s career as a successful, great heavyweight champion. You couldn’t have a better subject. He made everybody look good. He liked the camera; he never met a microphone he didn’t want to speak into, television camera, whatever it was.

I was a boxing fan before Muhammad came along. My dad was a fight fan and I used to watch Friday night fights with him as a kid on television. Some of my favorite sports pictures when I was getting interested in sports photography were taken by other photographers, of course, were boxing pictures.

It has a wonderful history and it’s a shame the sport is not what it once was. Ali was a wonderful character to be around. I always liked the excitement, the build-up to a big fight. Covering it, and being around a character like Ali, it was easy to fall in love with photographing boxing.

•••

As a young photographer, other than the times that I shot in the studio, I probably did 75, maybe even 100 covers for Sports Illustrated on subjects that I never so much as shook hands with. When you go to a game, you photograph the game. The hero of the game runs on the cover of the magazine. So except when they came into the studio to pose for a posed cover, I really didn’t meet them. Quite frankly, I can count on one hand the number of subjects that I’ve so much as had a cup of coffee with outside of the shoot.

Muhammad Ali posed for me many times. He doesn’t drink of course, but I never had so much as a soda or a cup of coffee with him until after he was retired. We’ve become very good friends over the last 20, 25 years. I spent a lot of time around Ali since he has retired. As a fighter, it was my job to photograph him. When you finish, you shake hands and thank the subject for posing and that’s usually the last you see of them.

I really didn’t get to know most of these guys personally. I photographed everybody from Mickey Mantle and Joe Namath, to President Ronald Reagan and you don’t have a lot of time.

Your job is to go there and do the job you’re sent to do. They’re not a whole lot interested in talking and I’m not a whole lot interested in anything other than the best possible picture I can get of the subject I’ve been assigned to shoot.

Then the shoot is over and usually, like I said, it ends very nicely with you shaking hands with the subject. I like to take pictures of myself, or have my assistant snap a picture of me with the subject because I always knew one day I would get a little older and I would want to look back at them, but that’s about it.

I don’t think most of them think about them. A photographer has the subject; you’ve lit them up. You’re in the studio or even if you’re in the Oval Office, you’ve got the president lit with strobe lights and it’s the perfect situation. Whether it’s the Dream Team or the cast of Rocky; I did a cover on Willie Nelson -- I actually did a cover on Clint Eastwood and Burt Reynolds once -- and when you’re finished shooting, you say may I take a picture with you and they always say yes. I don’t think they thought about it for a tenth of a second.

•••

It is hard work. The Olympics are a marathon. You go for seventeen days; long hours and very little sleep. No real chance to sit down and have anything to eat other than grabbing a hot dog between events. You have the morning events, events in the afternoon, during the day, and then there are events at night. Certainly if you’re trying to cover as much as you can, which is fun to do, certainly it was a lot of fun when I was much younger. I just enjoyed going.

I liked the competition; I liked the various events very much and I liked the competition with the other photographers. All of us are trying to get the best possible play in the magazine, maybe get the cover of the magazine. I enjoyed all of that. It’s the same thing with all the sports. To me, if an event interested me - there were events I would have liked to pay to go see if I could. So to be working and doing something I enjoyed was just that much nicer.

•••

I’m very, very, close friends with most of the photographers that were my biggest competitors. I worked for many, many years with Walter Iooss, a great photographer. We are good friends to this day, very good friends. A couple of the older photographers have passed away, but we were very close. I always tried to get along with people and I think I did a pretty good job of it.

At the end of the day, we were pretty competitive. I always respected certainly the caliber of photographers at Sports Illustrated and Time magazine, people you’d respect. When I moved to Time magazine - David Kennerly, Ansel Adams - they were people you’d respect. I mean these were pretty good shooters. I just respected them and there was no reason you wouldn’t be on good terms and be good friends once the job was finished.

You’ve got to remember you were travelling together with people; going on planes together, you’re in hotels together, and something like the Olympics, you’re together for three weeks. Of course you get to know people on a personal level, you’re working with them. We had a pretty good group of photographers and I was close friends with most of them and I still am.

Every single time, every single assignment you had to [jockey for position]. Look, there’s only one cover for a magazine, so if you’re covering an event, and for the big events there would be a number of photographers sure. Sometimes the positions were assigned by the picture editor, sometimes it was just a matter of jockeying for the best position.

We had a group of very competitive group of guys, but I think for the most part, we had a group with good integrity. I always wanted to get the best picture. I didn’t want to get published because I pulled a fast one on another photographer and got an edge on him. I wanted to get the best picture and therefore get published because my picture was the best one. We had a certain integrity to the job and I think that’s really important.

•••

I was in the lucky position, certainly in the second half of my career, where I had the right to say no. Everything I did were things that I wanted to do. I wasn’t sort of told you’re going to Detroit to shoot hockey if I didn’t think it was something I would bring my enthusiasm to and want to do. I was able to say no. All of the assignments I did, or at least ninety percent of them, were things that I really wanted to do and looked forward to and I enjoyed them all. I really did.

If you’re lucky enough to be able to – I’m not going to suggest I could pick and choose and by the way, most of my assignments, the essays I did were things I suggested. So I was walking in saying, here’s something I’m really excited about doing. The ‘Animals of Africa’ was a suggestion that I made. The prison essay I did for Time magazine was a suggestion I made. The aircraft carrier piece I did was a pretty big story I had suggested to the magazine. If you’re suggesting things you want to do, obviously you’re going to be excited about them.

•••

On the story of him sneaking into Yankee Stadium…” I was looking for a way – I couldn’t afford a ticket to the game, and even if I could, you couldn’t get in a good position to shoot pictures. I discovered early on, I discovered that every single Sunday, there was a veterans hospital and they would pull up – this is 1958, I was fifteen years old when I started doing this – stadiums were not built to accommodate the handicap. Today it’s the law that you have to be wheelchair friendly – in those days it was very hard to bring in someone in a wheel chair into Yankee stadium. It just wasn’t easy to get them to wherever you wanted to bring them. Today the curbs, every corner in New York, the curbs allows you to wheel it down, rather than bounce it over what used to be the curb.

In any case, with the stadium, I discovered that every weekend, there would be anywhere from 30 to 60 wheelchair Army veterans brought on busses. The busses would park right outside the visitor’s bullpen because you could just wheel, what was during the baseball season the visitor’s bullpen, and you could wheel the wheelchairs right into the stadium.

They would be actually on the field, just behind what would be the outfield end zone. They would line these wheelchairs along the wall out in the outfield. It gave the Army veterans a chance to see the game.

Well, they never had enough people to help them wheel in. They would come, as I’d say, with as many as 50, 60 wheelchairs. They would have seven, eight people to wheel them in. They were always happy – I wasn’t the only person… there were men who wanted to see the game there were some kids like I was – and I would offer to wheel in a wheelchair or two, make a couple of trips up and down the bullpen stretch, and help them. Then I’d stay on the field and wheel them out after the game.

It was hardly sneaking in, it really wasn’t. Believe me, if I could have snuck in, I would have. That isn’t something you can count on doing, and it isn’t something I did. I just was smart enough to befriend the people that sort of ran this program. By the way, once they saw that I was loyal, that I was there every week and I would not only wheel them in, but I didn’t just disappear once I got inside. Most of the other people who helped wheel the chair in, once they were in the stadium, they disappeared.

It’s a terrible spot to watch a football game from: ground level in the end zone… unless you’re trying to take pictures. For me, it was priceless.

It has been written so many times – it makes for a nice story. It just isn’t true. I was absolutely legitimate. Now what I did do, again, I wouldn’t call it sneaking in, but we weren’t permitted anywhere, but in the end zone.

You had to stay where the wheelchairs were. Well, during the season as it got closer to December, it would get very cold, as winters do in New York. They had big coffee urns so the veterans could have a cup of coffee during the game. In those days, there were two security guys sort of rent-a-cops on each sideline: one behind the Giant’s bench and one behind the visiting team bench. I would always bring a cup of coffee over to one of the cops by the Giant’s bench and so they would look the other way for a little while I took my camera out and shot a few pictures on the bench before I got chased away by the professional photographers. Then I would go back to my spot in the end zone. I mean it wasn’t necessarily sneaking. I got in quite legitimately.

It was fun. For a kid, it was great. As I said, I truly couldn’t afford to buy a ticket to those games, I just didn’t have that kind of money, it was the only way I could get into the game.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski

Adam Schefter

Adam Schefter

Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor

Frank Deford

Frank Deford

Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell

Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Bryan Curtis

Bryan Curtis Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga