I grew up in a little town in Ohio called Berea. I got interested in tennis as a kid because there were a couple of college courts behind our house. Every morning I had a wake-up call when I heard the “ping, ping, ping.”

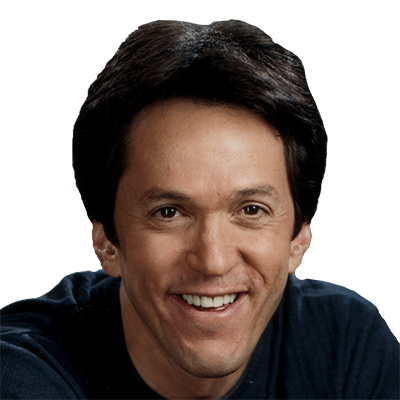

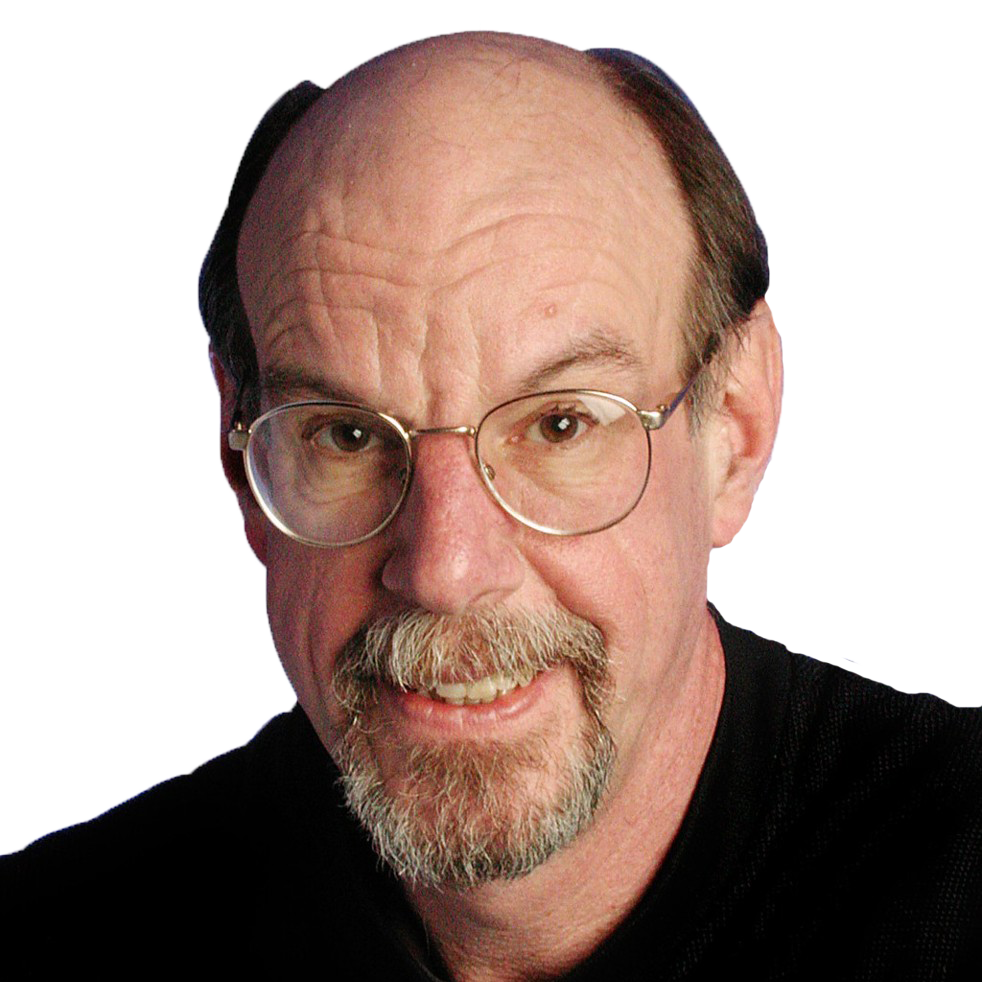

About Bud Collins

Arthur Worth “Bud” Collins, Jr. has been a fixture in the tennis community for over six decades and has become as well known for his newspaper and television work as for his colorful outfits and congenial personality.

BORN: June 17, 1929

HOMETOWN: Berea, Ohio

LIVES: Boston, Massachusetts

EDUCATION: Baldwin-Wallace

OCCUPATION: Columnist

TWITTER:

@budcollins

Read More

But I wasn’t really that crazy about tennis. I was more interested in baseball like all the kids at that age.

I began my newspaper career in Berea, with a weekly newspaper called the Enterprise. The publisher lived right next door to me and knew that I liked to write about things, so he hired me.

I covered a full page of the newspaper, high school and college games. I did that through high school, enjoying it very much.

During my college years at Baldwin-Wallace, in my hometown, I did some stringing for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. My big thrill in those early years was covering Harrison Dillard, the top hurdler in the world who also attended Baldwin-Wallace.

I was the sports editor of the college newspaper, The Exponent. When Dillard qualified for the Olympics, the editor of the college newspaper, Bob Beach, said to me, “Somebody should go to the Olympics.” And I said, “How are we going to do that?” He said, “Well, we’ll shake down as many relatives as we can.” We went to England and went to the Olympics in 1948, where Dillard won the 100-meter dash. It was the first of a lifetime of events I covered on the road.

(Photo Credit: Charlie Cowins)

I graduated from college and I went into the Army for a year. I went to Boston University to try to move around a little. I made a little money from my Army pay. I tried to save as much as I could and I got a job as a copy boy at the Boston Herald.

I enjoyed being a copy boy. My first assignment was a high school football game, which I earned $5. If I also served as a copy boy for the night, I earned $10, pretty good in those days.

I loved Boston and still do. I attended as many sport events as I could, writing sidebars from time to time.

The [Herald] sports editor, I guess he was pleased with what little I was doing, surprised me by asking me to join the staff. I was stunned. I had not anticipated that. Of course I accepted. He said we needed a boxing writer and boxing in those days was really big in Boston. He said, “Do you know much about boxing?” I said, “Of course.”

I knew nothing.

Tim Horgan, a leading sportswriter at the time, helped me a lot and even though I didn’t know a lot about boxing, I picked up a lot on the way.

We had a lot great boxers in Boston. It was a good assignment.

Tennis was not on my mind but one day the sports editor asked me if I knew anything about tennis. I said, “Oh, sure.”

I wasn’t really that fond of it because I was a baseball nut. Tennis didn’t really appeal to me. Although I played on the high school tennis team, I was not that good.

However, the sports editor asked me to cover a tournament at the Longwood Cricket Club. He said, “It’s a fancy place so be sure to wear a shirt and tie and just pay attention enough to write a good two or three paragraphs.” I was kind of thrilled because I knew that was one of the centers of the tennis world even though I didn’t know much about it.

That first tournament I covered was the Massachusetts Women’s Championships. I was introduced to a woman named Hazel Wightman, who was the founder of the Wightman Cup. She was a very prominent woman in the international competition.

(Photo Credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sdluvingit/5547868980)

When we were introduced, Hazel said, “I’m Hazel Wightman.” And I said, “I thought you were dead.” Because when you have Cups named after you, like the Stanley Cup, you were usually out of business. So that was a rather tense moment for my first assignment.

When we were introduced, Hazel said, “I’m Hazel Wightman.” And I said, “I thought you were dead.” Because when you have Cups named after you, like the Stanley Cup, you were usually out of business. So that was a rather tense moment for my first assignment.

People watching the matches on the clubhouse court were gasping when they heard that. I thought, “Well boy, I’m dead.” But she was a very kind person and said, “No, as you can see, I’m quite alive.” She became a great friend and was helpful to me in many ways, even proposing me for membership in the club.

The U.S. Doubles Championships was held in August every year. That year the boss asked me to cover it since “nobody else wanted to.”

On the third day of the championship, Hurricane Diane hit Boston. It rained and rained and rained. Eventually there was three feet of water on the court. I figured that was the end of my tennis career. “Don’t get the idea you’re going to spend a lot of time in tennis, because we got other things to cover,” the boss said.

(Photo Credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jacdupree/326201355)

One day the managing editor of the paper asked me about Althea Gibson. I wanted to act like I knew something about it, so I said, “She has a great chance” – a stock answer. He asked if I could get there to cover her matches at the U.S. Championships.

A friend and I drove to NYC together and shared a hotel room. Gibson didn’t win in 1956 but Ken Rosewall and Lew Hoad were vying for a Grand Slam.

I said to the boss, “We better cover that, it’s a big deal.” And he said, “It’s not a big deal for us.” So I went to the match, but I didn’t cover it.

In those days I was covering everything else too, the Red Sox, the Celtics and the Bruins. Boston is a great sports town, so it was a wonderful opportunity.

I never gave tennis much thought. I covered a couple of other tournaments, but as far as going to Forest Hill for U.S. Championships, no one at the Herald was interested.

My appreciation for tennis grew as I watched the tournament at Longwood. I tried to follow tennis as closely as I could, reading everything I could on it.

Benny Friedman, Brandeis’ first athletic director, had seen my byline on a couple of stories and wanted to start a tennis team. He asked if I’d be interested in coaching for $200 a season. I said sure and ended up coaching there for five years.

My first year there, I had the most famous college athlete ever on the team – [political activist] Abbie Hoffman. Abbie was one of the great rebels. He was very difficult as a person and a player. He wanted to run the show. However, we did have an undefeated season that year.

Tom Winship, the editor at the Globe, knew about me from my writing at the Herald, where I was a rising young writer. He called me one day in 1963 and invited me to lunch, luring me to the Globe along with Tim Leland. That was the start of my fifty years at the Globe.

I was a general sports columnist at the Globe, but people who ran the newspaper liked tennis, so I got to cover as much tennis as I wanted.

My first overseas assignment was to cover the 1963 Davis Cup final in Australia. The United States beat Australia and Chuck McKinley was the star for the United States. I think I was the only American writer there, so I just sort of fell into it.

(Photo Credit: Wally Gobetz)

My television career began on Boston’s public network, WGBH. We were pioneers, really, of tennis television. It had previously only been on once or twice a year.

Producer Greg Harney had seen my work in the Globe and asked if I’d like to telecast tennis. I asked him, “Why?” He said, “We think we can become something.” And I said, “Well, I don’t agree with that, but I’ll help you with whatever you need. It sounds like fun.”

It turned out to be very fun.

At first, we showed local matches and then progressed to the U.S. Doubles Championships. We did it on a nightly basis throughout Boston and then throughout New England. Finally we were broadcasting almost the entire tennis circuit of its day.

I began doing the commentary, and I just kept doing it for a long time. It was something totally unexpected in my life, and it’s probably the thing I’m best known for.

More people see you on the television than they read you. We reached people that never had any interest in tennis or television. We covered tournaments all over the world including places like Australia, Japan, Sweden and Italy.

After Arthur Ashe won the U.S. Amateur Championships at Longwood in 1968, I had an hour-long interview with him on PBS. That led to CBS asking me to work for them.

Together with Jack Kramer, I covered the first five U.S. Opens for CBS. In those days one could not really work for all the networks the ways commentators do now. At one point I had to choose between CBS and NBC. I was still doing PBS, which I kept on doing for many more years. I chose NBC over CBS in 1972 because they had Wimbledon. I worked for them for 35 years.

Many players became stars from being on television. We were the first to have Renee Richards and had her for a long TV interview when she played in New Jersey She spoke fearlessly about the trials and tribulations of what she had done. We also had Arthur Ashe a lot of times.

We were on PBS almost daily during tournaments and soon found out we couldn’t afford it. The solution was to tape matches and show them in the evenings. Nobody realized the matches were taped and the broadcasts grew in popularity.

I’ve had many highlights, including broadcasting the 1968 U.S. Amateur Championships won by Arthur Ashe in five sets over Bob Lutz. I also worked at the inaugural U.S. Open that same year when Ashe beat Dutchman Tom Okker in five sets. It was hugely significant and a thrill for me.

We also broadcast the completion of the tournament with Rod Laver and Tony Roach, where Laver completed his second Grand Slam. That 1969 tournament had been plagued with downpour of rain and it was a very hard match for Laver to win, but it eventually finished with Rod’s triumph.

At the Globe we tried to cover everything on the tennis scene and we covered the Red Sox and everything that was going on in Boston. I was a lucky guy. The audience grew for the tennis and I was covering lots of tournaments on weekends. I got to watch an awful lot of good tennis.

I also had a travel column, “ANYWHERE,” which ran bi-weekly for 25 years. The Globe then was starting to make its rise, and it was nice to be a part of that.

My writing style, I hope, is a variety approach. I use a lot of humor when I could; the feeling like sports wasn’t the end of the world. But I also have some serious stuff. I was lucky the Globe let me write the way I wanted to write.

My writing style, I hope, is a variety approach. I use a lot of humor when I could; the feeling like sports wasn’t the end of the world. But I also have some serious stuff. I was lucky the Globe let me write the way I wanted to write.

During my career, I liked to inform myself by reading other colleagues such as Barry Lorge of the Washington Post, Jim Murray and Bill Dwyer of the L.A. Times and George Vecsey and Neil Amdur from the New York Times.

There was also Ron Bookman, who helped Gladys Heldman run World Tennis Magazine. Gladys was hugely influential. I admired quite a few of the English writers. They spent more time on tennis than anyone else.

You didn’t have a lot of writers concentrating on tennis. There was a bit of tennis rush when the U.S. Championships came along in Forest Hills at the end of the season. Wimbledon drew a few paragraphs but not much.

During the Davis Cup weekend you sometimes had attention paid to it. A guy like John McEnroe did a lot for the game. So did Jimmy Connors, Martina Hingis, Martina Navratilova and the Williams sisters. It’s never been the highlight event, but sometimes it comes along.

Connors and McEnroe were fun to cover because of their temperaments. They weren’t going to be the great sportsman of the year, but they really attracted people with their lusty play you might say.

I don’t like the current game as much, because there’s so much ground stroking and not enough variety in the game. That bothers me a little. We need a little more variety in the game.

Today, you might go to see some matches where no one plays serve and volley at all. I felt very lucky to be associated at the same time with Laver because I think he’s the greatest player to ever live.

(Bud Collins with Rod Laver: Photo Credit: Anita Ruthling Klaussen)

I love the Australian Open and Wimbledon. I’m very fond of Newport, where the American game began in 1880. I like the Italian Open very much. The spectators are out of their minds and very nice.

When I started covering the Australian Open, it was an ordinary, not very attractive tournament, but now it’s tremendous. It’s gone past everybody in many respects, but now we don’t have any Australian players.

I’ve just had a glorious time. I’ve met so many wonderful people. And one of the best things has been meeting the foreign players that come in. It’s really a wonderful game that touches so many people and I just hope it keeps going.

I’ve just had a glorious time. I’ve met so many wonderful people. And one of the best things has been meeting the foreign players that come in. And it’s really a wonderful game that touches so many people and I just hope it keeps going.

There were not many people [in the media center at the U.S. Open]. You always had Allison Danzig and Al Laney – from the New York Times and New York Herald Tribune. Those two guys were the regulars and that was about it.

If you had a foreign player that was doing well, they might send someone along. Lance Tingay of the Telegraph of London came over usually; he was regarded as a top tennis writer in the world. But he didn’t come regularly; he would come every once in a while.

The press box was right on the court level at Forest Hills. The people who ran it were not very cordial to the press. So I tried to enjoy it.

I’ll never forget Danzig, who was a wonderful man. The players insisted on total silence while they were playing. They would play a point and then there would be applause. Danzig had a wonderful system for writing with his typewriter, and as soon as the point ended, Allison pounded away to get three or four words, “bang!”

(Photo Credit: Anita Ruthling Klaussen)

I marveled at that. I thought, “Gosh, how do you do that? How do even know who won the point?”

Newspapers are having a tough time these days, so writers have to scramble and try many avenues. The Internet is where it’s at currently. But there are still many good tennis writers today, including Steve Flink, Chris Clarey, Scott Price, Liz Clarke and George Vecsey.

My career advice would be to do a lot of reading. Find out what’s going on around the world, because it’s an international sport.

Good stories are never turned down if they’re good and if they’re different. Don’t give up on it. There are plenty of good stories if you can dig them out.

Try to read what you can. Try to travel if your editor will let you. Maybe you have to do a selling job and say, ‘We need this in our paper.’ It depends on who you work for and who your editor is. Jump in when you think there is a good story. Good stories are never turned down if they’re good and if they’re different.

(Photo Credit: Anita Ruthling Klaussen)

Don’t give up on it. There are plenty of good stories if you can dig them out.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor Frank Deford

Frank Deford Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga