JOAN RYAN

Biography

Joan Ryan, 54, was born in the Bronx in New York City. he attended the University of Florida, where she earned a degree in journalism with a focus on editing in 1981. She received her first job three days after graduation as a copy editor for the Orlando Sentinel, a job she thought not many people wanted.

She moved to San Francisco in 1985 as a full-time sports columnist for the San Francisco Examiner, where she covered boxing with the help of her husband, Barry Tompkins, a longtime FOX sportscaster. Then in 1994, the Chronicle hired her to continue writing columns and features for the metro section, but after her passion switched to longform journalism; thus, she took to a career as an author.

Her career as a journalist has earned her many accolades, including the prestigious Edgar A. Poe Award from the White House Correspondents Association, 13 Associated Press Sports Editors writing awards, the National Headliner Award and the Women’s Sports Foundation’s Journalism Award.

Interviewed by Megan Schneider

Igot started in Cleveland in 1964, ’63 maybe

The editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer was a man named Hal Lebovitz. He was very well-known and was the sports editor of The Plain Dealer for 15 to 16 years I guess.

He called me up one day and said that he had a good idea of having me write a sports column that he was going to call “Back Seat Brown” because at the time my husband was the quarterback for the Cleveland Browns.

The antecedent for that column was Charlie Conerly, the quarterback for the New York Giants. His wife [Perian Conerly] had written a column called “Backseat Quarterback.” She wrote a wonderful book by the way. It was a funny book. It was humorous. It was about the life of what the wives were doing.

So I accepted Hal Lebovitz’s offer and later found out that he had assigned Chuck Heaton, the main sportswriter for the beat for the Browns, to standby and ghost write my column if that became necessary. It didn’t become necessary and I continued writing that column for quite a long time. I also submitted on spec columns for the Houston Chronicle and the Houston Post. At that time, we had lived half a year in Cleveland.

Then in 1970, we moved to Washington, D.C. I called up the Washington Star, and the sports editor Dave Burgin said that he had actually been advised to call me and invite me to come in for an interview. He hired me. For a number of years, I wrote two columns a week for the Washington Star. This involved covering the Billie Jean King-Bobby Riggs match at the Astrodome in Houston.

I wrote about whatever I wanted to write about and I came up with odd things, like left-handed female bowlers and what happens to the pole vaulter when they travel to an out-of-town meet on an airplane. I think people enjoyed the variety that I came up with. I covered professional sports. I wrote about pro basketball, college basketball, pro football, and college football.

I did not ever go into the locker room because I was married and I had four sons. I knew that even among my sons, some of them were more modest than the others. A man confronted with a woman who he doesn’t really know is put off-guard in a way that I thought was unfair.

So I managed to deal with that cross to bear by phoning ahead, if it was a football game per se, and telling them which players I wanted to speak to. They would arrange a private room and I would talk to the players when they were dressed and ready to leave. I happen to think that I got better stories because I had the one on one and they had to stay.

I remember one famously. I was interviewing Billy Kilmer in the dugout of Redskins Stadium and he was recounting another heroic come-from-behind victory. So I don’t think I was in any way diminished by not going in the locker room.

Now, the press box, when I was first started writing in the ’60s, women weren’t allowed in the press box. The press box is an important place to be able to go into because that’s where they rattled off on the loud speaker system whose 178th time that so-and-so did this, the sort of statistic that nobody would ever expect a lowly sportswriter to have at their fingertips. So it’s much more important to have access to those sorts of statistics.

I don’t know why they didn’t allow women in the press box, but I remember I was at Cleveland stadium and I had arranged to write about the cameras that they had. It was the very beginning of slow motion and reverse, where they would show the progress of the football play and then they could reverse it and show the players going backwards. So I was writing a piece about the technical photography and sound, including the microphone placement, what have you.

I remember the CBS people had to walk through the press box to get to the roof of the Cleveland stadium where some of their equipment was, so they had to lead me through the press box. One had a manila envelope in his hand and he put it up over my face like there might be something going on that he didn’t want me to see. I did think that was really silly and I think I managed to write that into the piece.

There were other women reporters in the United States, but there weren’t very many. There was a woman [Mary Garber] in Winston-Salem who was the editor of the society page [for the Twin City Sentinel]. This was in the ’40s. When all the men went off to war, she became the sports editor and, I’m sure, head of the whole sports department. She covered all the college sports because it was much bigger then than the pro sports were. But when the war ended, she continued to cover basketball and college football and became a beloved figure.

Of course sports, just like any other endeavor that people take on, has a certain lingo, a certain set of rules and vocabulary, a certain season and a certain high point and low point. Anybody could have done that. There’s no reason why women can’t understand professional sports, or professional football as easily as men, but they did kind of act like it, that we were separate from everything.

One of the fun things about writing about sports is that every one of them is different. It’s like you have to learn a new language. I have two sons who rowed in college with great success and the jargon for rowing is a language unto itself and it has its heroes.

Most recently, their rowing coach at Harvard just died last spring. About 2,000 of his rowers came to Cambridge to row on the Charles River to honor his life and not only did they collect in Cambridge, but also a group gathered in England on the Thames with the Oxford-Cambridge race being one of the hallmarks of rowing. Another group gathered in Australia. Harry Parker — that’s his name. Both my sons went when he died. He had the biggest influence on their lives with anything that they’ve ever experienced.

Sports have a way of touching people.

I ended up meeting Renée Richards on the first tournament that she played in after coming out as a transgender female. It was in South Orange, New Jersey. She was a medical doctor. She had gone to Yale and my husband and I had spent 14 years at Yale. He was athletic director and a member of the math department and I worked with the publications of the Yale School of Management and also the university newspaper.

But anyway, she had been retired from being a doctor. She was an ophthalmologist who had actually discovered and perfected a special kind of surgery to correct crossed eyes until then. She told a very touching tale of a friend of hers who was a mathematician who had committed suicide because of the kind of homophobic type of reactions. This friend of hers had felt completely blocked in and that she felt she was making a stand for this friend by undergoing really dramatic physical changes in her body and undergoing some rather traumatic surgeries.

She then of course went on to commit herself to tennis. I think she was for a while a coach for Martina Navratilova. But it was a very touching interview and I was very moved by it. Several of my friends have always told me that that was their favorite article.

I also had to be very careful not to insult any of [my husband’s] teammates or say anything blatantly ridiculous. I did have one terrible moment when I had written a column saying that one of the players on the Browns team thought [Dallas Cowboys quarterback] Don Meredith was a loser. I had written that and said that my husband had been ridiculed. He couldn’t believe his teammate would say such a thing. That was just not true.

I thought I covered myself pretty well until we went down to the game, and I actually happened to go with my husband on that trip. They booed my husband in the Cotton Bowl [stadium] in his hometown in Fort Worth, Texas. Fort Worth, Dallas. Fort Worth is where he’s from. So I was really rather upset by having exposed him to the fans, not meaning to and certainly not believing it myself. But the teammate of course still maintains that he was right.

Anyway, that was a very difficult thing but it certainly was a tribute to my husband after the game. Instead of apologizing to him, he said that I really think it’s better to climb up the tree and crawl out on the limb than to stand on the ground and just look up. So I did kind of climb out by myself. But we recovered and ended up being friends with Don Meredith. He is a lovely man. He died a few years ago but his career was somewhat expanded by being such a colorful color man on Monday Night Football.

But when I watch football today, I don’t recognize it. It’s completely different from the teams that my husband played on and the generation that we come from. It was much slower. It was a more stolid game. My husband, who was a quarterback, still holds at least one NFL record, in fact: the highest percentage of touchdowns per pass. His statistics after an average game would be that he might maybe throw 18 passes or 12 passes. It’s not like today where they throw passes that sometimes don’t even travel six inches. I mean a lot of passes that the quarterbacks throw don’t even make the line of scrimmage. It’s like they’re playing catch with each other in the backfield.

Then, the players are taller. They’re stronger. Particularly, the defensive backs are bigger. They’re like they have springs on their feet! They jump. They leap into the air. They jump up and down and celebrate. They bang each other’s helmets and they just moved the ball forward a yard and a half! In Frank’s era, it was cool to just toss the ball behind your back to the referee after you scored. This was before spiking. But I still watch and so does my husband. I’m for Peyton Manning. I’m rooting for the Broncos [to win the Super Bowl this year].

I went to the Rice Institute in Houston. It’s very small but a very difficult school to get into and even more difficult to get out of. It was sort of a Cal Tech, MIT-type school. It specialized in engineering, mathematics, physics, chemistry, but it did have a liberal arts program. The ratio was five men to every one woman. Rarely was a woman enrolled in engineering. I think there were two in my class, who got degrees in mathematics or engineering.

(Photo Courtesy of Joan Ryan)

I took a liberal arts program, although you were required to take two years of science, and so my degree was in English literature. I think that prepares you better for writing about sports. I read about anything to take liberally from great books – history, Shakespeare, history a lot – because I think it kind of transposes almost into almost anything you kind of write about – politics, whatever. It gives you a grounding in human behavior – human hopes and wants and despairs.

[I graduated in] 1958. It’s now called Rice University in Houston.

I got married. Frank and I moved to Los Angeles in 1958. He played for the Rams for four years and I began raising our children. We have four sons.

The early ’60s was the first job I had, which was writing. I remember Dave Burgin telling me that people were looking for women to write about sports in the early ’70s when we moved to Washington. I don’t know why but every major newspaper thought it was really slick to have a woman’s name on the sports page.

Dave Burgin told me that he had hired a woman from the style section because she had written an article for the style section about tennis. So he called her up and asked if she could move over to the sports section. Then he said, “She wrote about three or four more articles about tennis and then she just ran dry.”

He said, “The thing I like about you is that you always come up with something new to write about.”

So they didn’t have to worry about me. They didn’t have to assign things to me. They just let me.

Except now George [Solomon] did! George wasn’t a real sports editor to me. He gave me assignments. I just adored George Solomon and his wife, Hazel. She’s really one of the funniest people I’ve ever met.

My favorite George Solomon story is he called me into his office and he said, “Now Joan...”

His office had a big window behind his back that looked out onto the Russian embassy, so it was always kind of scary to go into his office because it was sort of at the end of the Cold War. You weren’t sure whether they were spying into George’s office from the Russian embassy. I’m making jokes. Of course they weren’t.

But anyway, I’m sitting on the other side of George’s desk, and he said, “Joan, I’ve got the best assignment in the whole sports year and I’m giving it to you!”

And I said, “Oh George, thank you!”

He said, “I’m going to send you to the Indy 500.”

Then there was this silence and I think he thought I was going to jump up and give him a kiss on the cheek.

I said, “Now George, let me just ask you something. Is this where they have those little vacuum-cleaner cars or is this where they have these souped-up Chevrolets?”

I thought he was going to jump out the window and surrender to the Russians! I’m telling you. I’ve never seen the look of fright on anybody’s face.

All he could do was say, “Joan, please don’t embarrass The Washington Post.”

I said, “George, don’t worry. By the time I get there, I’m going to know the difference.”

It was fabulous [covering the Indy 500]. Actually, The Washington Post had broken the female barrier the year before by sending Myra [MacPherson]. She was married to a sportswriter from the Washington Star. She was a very pushy and forward, brash-talking woman, four letter words and all that kind of stuff. They didn’t allow women into the brickyard, but of course they did allow her in.

Then of course, the next year rolled around. I’m sure there were other women there. I didn’t see any but it was lovely. I had the regular slacks and jacket outfit for walking around in the dust, but I topped that with a great big, round circular straw hat that I had bought in St. Bart’s. It had straw butterflies. I wear hats anyway because I have a pale complexion and I didn’t want to get sunburned. But I picked this hat because it was an unmistakable lady hat.

For the first day or two that I was there, and I was there for five days, I just walked up and down the alleyways and it was a whole new world. I was discovering things every time I stopped to talk to anybody and by the second day, people would come up to me and say, “Aren’t you the woman from The Washington Post?”

“The woman in the hat!”

(Photo Credit: James Atherton/Washington Post)

I got such great stories out of all these people and I was filing them out on a daily basis to George and George was putting them out on the wire service that The Washington Post shared with, in those days, it was the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post. But they had a shared syndication.

So every day I would wake up and the Indianapolis newspaper would have my stuff on page one! I loved it! Not page one of the sports section but page one of the newspaper! So I knew I was coming through for George and not embarrassing him.

So that was the only time I’ve ever had an argument with George.

The morning of the race was supposed to have this big takeout, this big long piece that ultimately predicted who I thought was going to win and George was just adamant that I should pick Mario Andretti, and I said, “No, George, I just really can’t do that in good conscience.”

I think George thought I didn’t know anything because I had compared the cars to little vacuum cleaners. So I said, “No, it’s got to be A.J. Foyt.”

But he very reluctantly just talked me through it quickly and said, “OK, Joan.” He allowed me to pick A.J. Foyt and A.J. won. It was his record fourth win.

So when I got back, I asked him, “Where is the confetti? I thought you were going to greet me with it! Throwing confetti all over my desk.”

It was shortly after that we moved to New Haven and I continued to write. I was syndicated with The Washington Post Writers Group, but it was difficult because I was writing one column a week and it was delayed. I would turn it in on a Monday and it would be ready for use the following Monday, and you can’t write sports that way because it’s just too immediate.

I had been syndicated when I was with the Washington Star with the Newspaper Enterprise Association. That lasted for quite a long time. It was about four or five years. They did wonderful little cartoons and line drawings for each of my columns and Ira Berkow, the leading sports columnist for The New York Times, was my editor and he and I became telephone friends.

Nowadays, of course you’ve got blogs and things that are an instant technology transfer and I was just a little bit ahead of my time. I had quite a lot of people and quite a number of newspapers that were loyal to my column that I could’ve kept it going on my own had I changed the deadline. But it was at the very beginning of faxing, so to fax something was really considered the quickest way. You didn’t have wire transfers the way they do now. So I was just before my time.

I write for the Grafton News. We live in a little village of 500 people. I write about the migration of butterflies and the problems with the bees dying off. I’ll probably write about the deer I just saw at the top of my hill. I wrote about Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee. I try to usually have a little humor in it. A lot of people really enjoy it. It’s better than just reading about the cost of salt for the road. But we have to move the town garage because it was damaged by the hurricane two years ago so that’s all they write about in the newspaper. So everybody gets excited if I have a column in there.

Red Smith, Shirley Povich, James Thurber, E. B. White – people who could write with humor and perception and make a point and strike a nerve.

Red Smith was with The New York Times, and Shirley Povich had just retired (briefly) from The Washington Post when I was hired, but he still came to the paper every day whenever I was there, unlike me. I didn’t come every day because I was out interviewing people but whenever I was there, he would always come over to my desk and he would sit down and we would talk about Shakespeare. He was just a really wonderful man.

I’m a big fan of E. B. White too. He’s, of course, an essayist, the No. 1 essayist for the New Yorker magazine. I love Thurber’s writing, although he got kind of sad and bitter at the end.

I don’t think you can differentiate between sports writing and any other kind of writing. I think good writing is good writing. I’ve read things that E. B. White wrote about sports that were as good as anything Red Smith wrote about sports. Certainly, I read things that Red Smith wrote a while ago about sports that were beautifully written and struck a point.

When I was involved in what was the creative writing of sports, I mean columns and things that were supposed to have a beginning, a middle, a transfer and an end, they were supposed to have humor or insight, or something that led the reader to look at a sports event or a sports personality in a different way. But for a beat reporter, I don’t think I would’ve been entranced if they had assigned me to cover some hockey team and that was all I did – report on the same 15 or 20 people, playing the same games over and over and over again and the times to mix stuff up during the season when they weren’t playing. It’s a different thing.

Covering a game is like writing in reverse. You’re writing the first part of the game as though it’s the last paragraph in the article as it appears, but when you turn it in, the desk back at your newspaper takes it and sort of sticks it at the bottom. Then they keep putting these building blocks on so that the last thing you write is the whopping beginning where you tell what has really transpired – who won, the way it was a brinkmanship or it was a come-from-behind. You come up with the best definition of an eye-catching opening. But as you go through and read even something today in the newspaper, it is written as though it’s written backwards. You get down to the bottom and you read that last paragraph and you think that this doesn’t seem to have an end to it. There’s no finale, which of course in a column, you end up writing a finale.

So anyway, I like the creative aspect of spinning a tale, describing the personality, getting somebody to say something that gives some sort of insight. There were a couple of times when I protected players who said things that I thought would get them in trouble, and I never told the editors that I worked for that I did this. But I edited things out of my notes that would’ve been inflammatory and it would’ve been a heckler for me, but at the same time it just seemed unfair because I was older than they were and I knew it would have repercussions that I didn’t want to be responsible for putting on them.

It was fun. It was just fun all the time. It was a job that I couldn’t wait to get up the next morning and get back to. Yet, there was always this pressure of having somebody you had to interview in order to complete your story. Would they speak to you? Would you be at the right place at the right time and be able to get the interview? I was so, so lucky because I never, ever, ever missed getting to the person that I needed to get to for a story. I was just very blessed that way, so it ended up being a very rewarding and rich career.

Sportswriters are funny too! They sit around and make jokes, and athletes do too. There’s a wonderful band of humor that runs through all sports. I guess you have to laugh because sometimes it hurts. The losing hurts.

Your assignment, should you care to take it, is to go on your machine and Google John Stevens’ song on Peyton Manning. It’s written by John Stevens and he performs it and it has the refrain, “I think she loves Peyton Manning more than me!” about his girlfriend. It will give you a laugh!

JOAN RYAN

Biography

Joan Ryan, 78, launched her career as a sports journalist when her husband, Frank Ryan, became the starting quarterback for the Cleveland Browns. However, when she graduated from the Rice Institute in Houston, Texas, with a degree in English literature in 1958, she did not know that she would write about sports. The Ryan family then moved to Washington, where her husband played for the Washington Redskins during the 1969 and 1970 seasons. Here, Dave Burgin, the sports editor of the Washington Star, sought her out to cover sports at both the college and professional level.

She then was a member of the sports department at The Washington Post under sports editor George Solomon, where she was a columnist and also reported on the famous Indianapolis 500 in which A.J. Foyt earned his fourth title for this race, a record that remains unbroken.

Igrew up in a family of six kids — three girls and three boys.

In his 1973 book "No Cheering in the Press Box," author Jerome Holtzman chronicled the lives of the greatest sports journalists of his generation. Four decades later, students at the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism are updating his work with a series of interviews with the best sports journalists of the last 40 years.

The chapter was produced by Megan Schneider

“A Gold Medal in Maturity.” The New York Times, April 5, 2009

“Risque Business.” San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 1, 2002

“Alcohol is a much bigger problem than steroids.” San Fransisco Chronicle, March 24, 2005

“Is it time to legalize steroids?” San Fransisco Chronicle, Feb. 20, 2004

My father was born and raised in the Bronx. Actually, I was born in the Bronx too. He was a Yankees fan, so I grew up mostly watching them. I would watch some games with him but I was not a diehard sports fan. I stretched the imagination. But I liked playing sports.

So my father coached all six of us in our sports – baseball for the boys and softball for the girls. He was our coach. We played it every day, and that was the thing: We lived our lives down at the ballpark with our father.

He was a little league coach for the boys and a softball coach for the girls for us — three girls and three boys. He coached all of us for whatever team we were on. Then he kind of specialized in girls’ softball because we were much more coachable. He liked coaching us. So I grew up playing that and loving it. The way he coached so many of us, it made us strong.

Education was not a real big value in my family because my dad didn’t graduate from high school and my mom graduated from high school but she worked as a cashier. My dad was a draftsman and in sports, my dad was the feather of the family. Sports were the most important thing to him. That’s how you got your strokes. That’s how you got attention as one of six kids, where you don’t get a whole lot of attention.

I’m third, so you’re really invisible as the third of six. I was really quiet and really, really introverted. I just read. I was a huge reader. I played sports and I was always a good student, and they liked that I was a good student, but my dad would rather I go four for four and make the diving catch in left field than get straight A’s. He would get much more excited about that. So anyway, I played softball through high school. I didn’t play in college. I wasn’t good enough for that.

(Photo Courtesy of Amazon.com)

I knew I wanted to be in journalism. I was editor of my high school paper, but I never even considered writing about sports. I didn’t grow up thinking that. I thought I would like news, feature stories, that sort of thing. Actually, I didn’t even think I was going to write because I was so introverted and shy that I wanted to be an editor behind the scenes.

Launching Her Career

When I majored in journalism in college at the University of Florida, I basically majored in editing and I worked maybe one or two semesters for the school paper and I didn’t write anything. I just wrote headlines and edited copy, which was fine. Of course I had a really easy time getting a job because who else wants to do that?

But then I thought if I want to move up in the newspaper business, I better have some writing experience to eventually be editor of the paper, which of course, that’s what my ambition was. Because I grew up reading the sports pages, I thought the best writing day in and day out was in the sports section. I really wasn’t excited about going to cover garbage strikes or city commission meetings. I thought, well, it would be fun maybe to write about sports and thought it would be interesting because it’s something I could talk to my dad about.

There had never been a woman in the Orlando Sentinel sports department. It hadn’t really occurred to me whether women did this or not. That wasn’t really on my radar. The editor of the paper at that time was a guy named David Burgin and was very much about what’s driving readership into every section. He thought having a woman in the sports section would make women maybe at least stop at the sports section – women who weren’t already reading it – and say, “Oh, well this could be interesting!” So, before I knew it, I was in the sports department.

He just heard about me. It got back to him that there was this young woman on the copy desk who was talking about writing sports and the light bulb went off in his head. Like I said, all of a sudden, I was in the sports department. I walked down there mostly to do copy editing at first and then I was sent out on a feature story here and a feature story there.

When one of the columnists went on vacation, the editor of the paper who had put me in that department said, “Why don’t you write a column?”

This guy was a huge golfer, and I wrote not thinking about that. He was also very explosive, could have an even abusive personality. I wrote this funny column about how golf wasn’t a sport, just poking fun at it.

The guys in the sports department were saying, “Are you sure you want to put this in there?”

Golf was the most important thing to Burgin — the most important thing.

And I just said, “Oh, come on. It’s just funny and I think it’s OK. How could he get upset about it?”

So, the next morning the paper comes out and my phone rang. It’s Burgin on the phone calling me at home and I’m thinking, “Oh my God, I just lost my job.”

He says, “I read your column. You know I disagree with every single sentence in it and I’m giving you a $50 a week raise because it was really brave and it was really well-written. We’re already getting mail about it!”

So that’s how I kind of launched my career.

Hardships Facing Female Sports Journalists

But what really happened, I still wasn’t thinking I was going to stay in sports. The thing that ended up happening was at that point the only professional sports team in Orlando was the USFL franchise, the Orlando Renegades, and I went out there to cover a game, actually just to do the sidebar on the opposing team, the Birmingham Stallions. By halftime, I already knew what my story was going to be because Joe Cribbs, who was a big NFL running back, was on the [Birmingham] Stallions and he had broken his wrist so that was going to be my side bar.

I don’t know if I had been in a locker room before. Maybe I had been in Tampa Bay’s or the Miami Dolphins’. But it was one of the first times I’ve been in a locker room. I went down there and pushed open the door, and I’ve been in a lot of those old stadiums and ballparks. You walk in onto this path. On one side are the lockers and on the other side are the bathroom and the showers.

(Photo Courtesy of Joan Ryan)

So the guys are just walking back and forth across your path as you walk in. It took a couple of seconds for them to register that I had walked in and then there was just this pandemonium, like “Oh my God!”

I was the only woman in there. Just yelling. I’m just so introverted. It’s such a bizarre thing to think that I even went into this business when I look back on it. But I was just mortified, absolutely mortified. I think my brain just shut down. I really don’t remember what they said. It was just like you were the scrawny kid on the playground and everybody’s just yelling at you and laughing. All eyes are on you, which is just the most painful possible thing for somebody who’s so introverted.

I was standing there and all I remember asking was, “Where’s Joe Cribbs’ locker?” Because I was on deadline.

Right next to me was a row of lockers with a bench and one of the football players was sitting there, and he, like all of them do, had his ankles taped up with five miles of tape. He had one of those long-handled razors that they use to cut the tape off, and all of a sudden I feel the handle, not the razor part, but the handle of the razor going up my leg because I was wearing a skirt. It was going up my leg. At that point, I just lost it.

I just screamed at the guy, “What are you doing?” and I just turned around and left. This was probably either ’83 or ’84. My editor ended up making me write a column about it and it’s been written about in other places.

I turn around to leave only to see in the doorway a man standing there with one of the red V-neck sweaters that all the coaches wore, and I thought, “Oh my God.”

He was just standing there laughing at the whole thing. He thought this was extremely amusing. Only to find out that he actually was the owner of the team. I found out later.

But anyway, I walk out, get the PR guy, and say, “Look. You’ve got to get Joe Cribbs for me because I’m on deadline.”

I ended up talking to Cribbs and writing, I’m sure, a pretty bad story. I went up to the press box and it was at that point that I pretty much decided I was going to be a sportswriter because it was so clear that they didn’t want me there and that they were just so abusive. And so I joke that I spent my whole career up there. But almost, in some way, that’s somewhat true.

As introverted and as shy as I was, I was super, super competitive, and I just thought, “No, they’re not going to win.” That’s just completely wrong with what they did and how they treat women.

So I ended up staying 13 to 14 years as a columnist and a feature writer. I found that I loved being out of the office. I loved writing about athletes and games and the drama and all the rest of it. The truth of the matter is being so introverted, having that notebook and pen in my hand was like a passport. It’s almost like this permission slip to not be me. I can be somebody else when I have this notebook and I can ask anybody anything that I wanted. I still never raised my hand at a press conference. I’m not sure I ever did, maybe toward the end of my career, but rarely. I can probably count on one hand how many times I asked a question at a press conference because I would get so embarrassed. But one on one or a small group, I was fine.

I was coming in at the same time that kind of across the country, women were coming in. Even in Cocoa Beach – Melissa [Isaacson]. She’s now in Chicago. She was working for the Cocoa Beach paper and she might have been at that game covering the Renegades, but she wasn’t in my locker room, the one I went into.

Christine Brennan was at the Miami Herald. So in Florida, we did have a few. I rarely saw another woman at any game I went to, but I knew they were out there. Then, actually, when I went to the U.S. Tennis Open, or covered tennis in Florida, there were always other women because tennis was one of those sports that women covered.

Then, when I came to San Francisco, rarely would I go to an event and there weren’t other women. There weren’t other women columnists, though. The women were mostly feature writers and some beat writers. But out here, I had Ann Killion, Susan Fornoff. Sally Jenkins had been out here, but not when I was here. She was here before me. Who else? There were quite a few. I can’t remember them all of them at that point, but you did feel that we were lucky enough that we had really good organizations that didn’t tolerate guys harassing us. It happened, but it was addressed right away.

Memorable Stories

Leonard-Hagler was probably one of the most exciting things I’ve ever covered because Leonard was making yet another comeback and Hagler was so favored to win that fight. It’s like the Super Bowl. You go there a week ahead of time and you do all these stories. I had a one-on-one interview with Ray Leonard, who actually was invited to my wedding because my husband is a sportscaster and worked with Ray at HBO doing boxing.

But so I sat down and talked to Leonard and I remember the interview with him and asking him why he was coming back.

There’s so much about athletes. It’s so hard to leave the arena because you’re so good at what you do and you still feel like you can do it. He was trying to make the case that he could’ve left, that he didn’t really need boxing and that he was doing all these other things in his life.

I remember asking him, “What are you doing?”

“Oh yeah, I’m taking these classes.”

“Oh really? What kind of classes?”

He turned to one of his guys and says, “Hey, what was that class I was taking?”

And the guy says, “Electrical engineering!”

“Oh yeah! Electrical engineering!”

It was almost comical.

Then Hagler kept talking about how he had nothing for thoughts.

He said, “If you crack open my head, instead of a brain, you’ll see a boxing glove.”

He was so committed and the stakes were so high for him because he was supposed to beat Leonard, and he lost.

(Photo Courtesy of Joan Ryan)

So that was fun. But also the Calgary Olympics, covering Brian Boitano, who was a local San Francisco guy and just put on one of the most perfect long programs in the history of the Olympics. It was just so joyous what he had accomplished.

Her Career as an Author

I also remember the Atlanta Olympics because my book had just come out on gymnasts and figure skaters, “Little Girls in Pretty Boxes.” I was just the devil in the gymnastics world. I was just hated in gymnastics, and of course, I went to the Olympics to cover gymnastics. None of them really knew me personally, except that I remember at a press conference, this was one press conference where I did ask a question, and all the gymnasts were sitting up at a desk.

Márta Károlyi, Béla’s wife, was the coach for that team and they were all spread out there, and I raised my hand to ask a question, and you could see, starting at one end, that one gymnast realized that, “Oh my God. It’s me! I’m the one!” You could see them whisper to the next one to the next one to the next one, “That’s her! That’s her!”

It was just like, “Oh wow.” I had become very notorious for being this horrible woman who was trashing their sport.

Before the 1992 Olympics, the Barcelona Olympics, and I wasn’t covering that, but six months before, I was thinking about stories leading up to that Olympics. My sports editor at the time, Glenn Schwarz, and I were brainstorming and I thought, “You know, we really should do a story on sports in which girls can be the best in the world while they’re still girls.”

That just never happens with boys because in every sport, except for maybe diving, boys have to go through puberty in order to compete at the highest level, whereas for girls, it’s different in sports. Puberty is the death row. They’re over.

So I did a series of stories for that, looking not only at gymnastics and figure skating, but also tennis and swimming, because you could be 14 or 15 and be the Joe Montana of your sport.

Then an agent came to me and said, “Wow, this is really provocative and interesting. Why don’t you think about doing a book?”

And I just go, “God, I can’t even imagine doing a book.”

She says, “Let’s just do a proposal. We’ll take you out to lunch.”

With my Irish-Catholic guilt, once you take her out for lunch, I guess I better do this proposal.

Then, she said, “Well, why don’t you rewrite this proposal?”

So she kind of kept pushing me, and then all of a sudden, I had a contractor for the book and then I had to do it. We decided that it made sense to focus on gymnastics and figure skating because they had the most in common. Also, so little had been written about those two sports. We already knew a lot about tennis – the Jennifer Capriatis and Andrea Jaegers and those people. We didn’t know about the gymnasts and figure skaters.

So that’s how that came about. It really created a firestorm. The biggest challenge of that book really was to make sure my facts were right because I wasn’t a gymnast or a figure skater and I didn’t even cover it that much. I knew if even one fact was wrong, they could dismiss the whole book. Luckily, there wasn’t.

The Tara VanDerveer book, “Shooting from the Outside,” came after the Atlanta Olympics, when she coached the gold medal basketball team. That was more of a how-to book, so that’s really more her book than mine. But I wrote it.

“Freak Season” is really not a book book, just a photo book that my friend Deanne Fitzmaurice did and I wrote all of the copy for it. But it was mostly like cute captions.

“The Water Giver” is about my son having a brain injury in 2006 and basically raising him and having a second chance, and it’s really what ended up partly prompting me to leave the Chronicle because I was gone for about nine months taking care of him. Then, when I went back, I didn’t want to write a column anymore. By then I was in news and was just tired of writing columns. You just get beat up too much and you just don’t learn enough. When you’re writing a column, you just really hope you’re right because you’re writing about stuff that you just don’t know that much about, and then the next day, you’ve got to write another one. The paper just wasn’t doing long-form journalism and that’s what I wanted to do.

So I got the contract to write “The Water Giver” from Simon & Schuster after I left the Chronicle and I just finished another book that was sent to the publisher, also Simon & Schuster, that I’ve written with Bengie Molina, a former catcher for the Giants. It’s written in his voice, sort of, about his father, who was a poor factory worker who raised three sons with Bengie being the oldest. All three became catchers in the Major Leagues and each one of them has two World Series rings. So it’s really about this man in this poor barrio in Puerto Rico, who he was and why he was just the hero to these three incredibly accomplished baseball players. They see their father as better than any of them but didn’t go to the Major Leagues, and Bengie finding out why his father never went to the Major Leagues. But that should be out next year, I think.

I just finished that one and I’ve been collecting research for three years on the next book, which is another baseball book, but I don’t want to talk about it yet because I don’t have a contract.

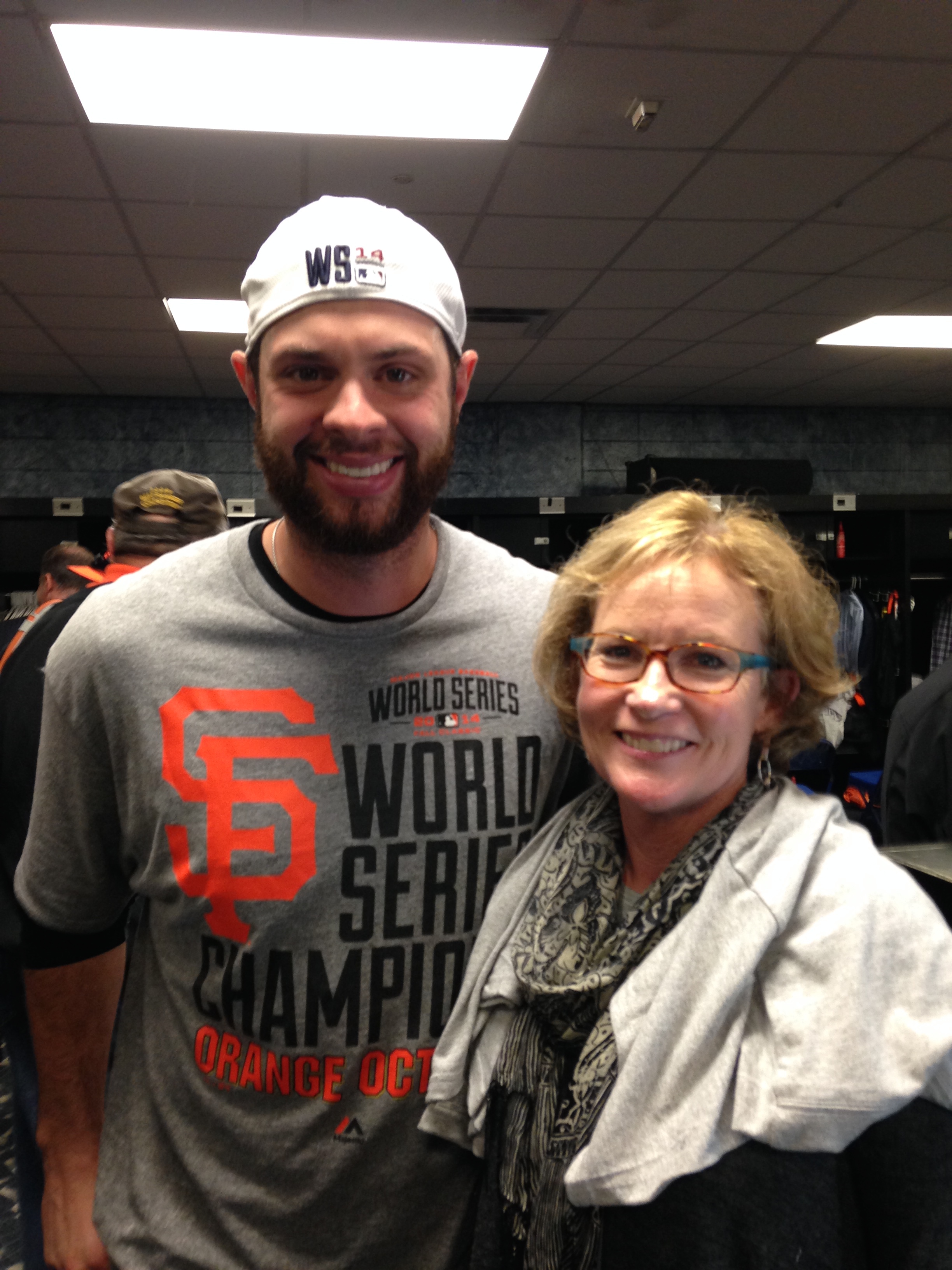

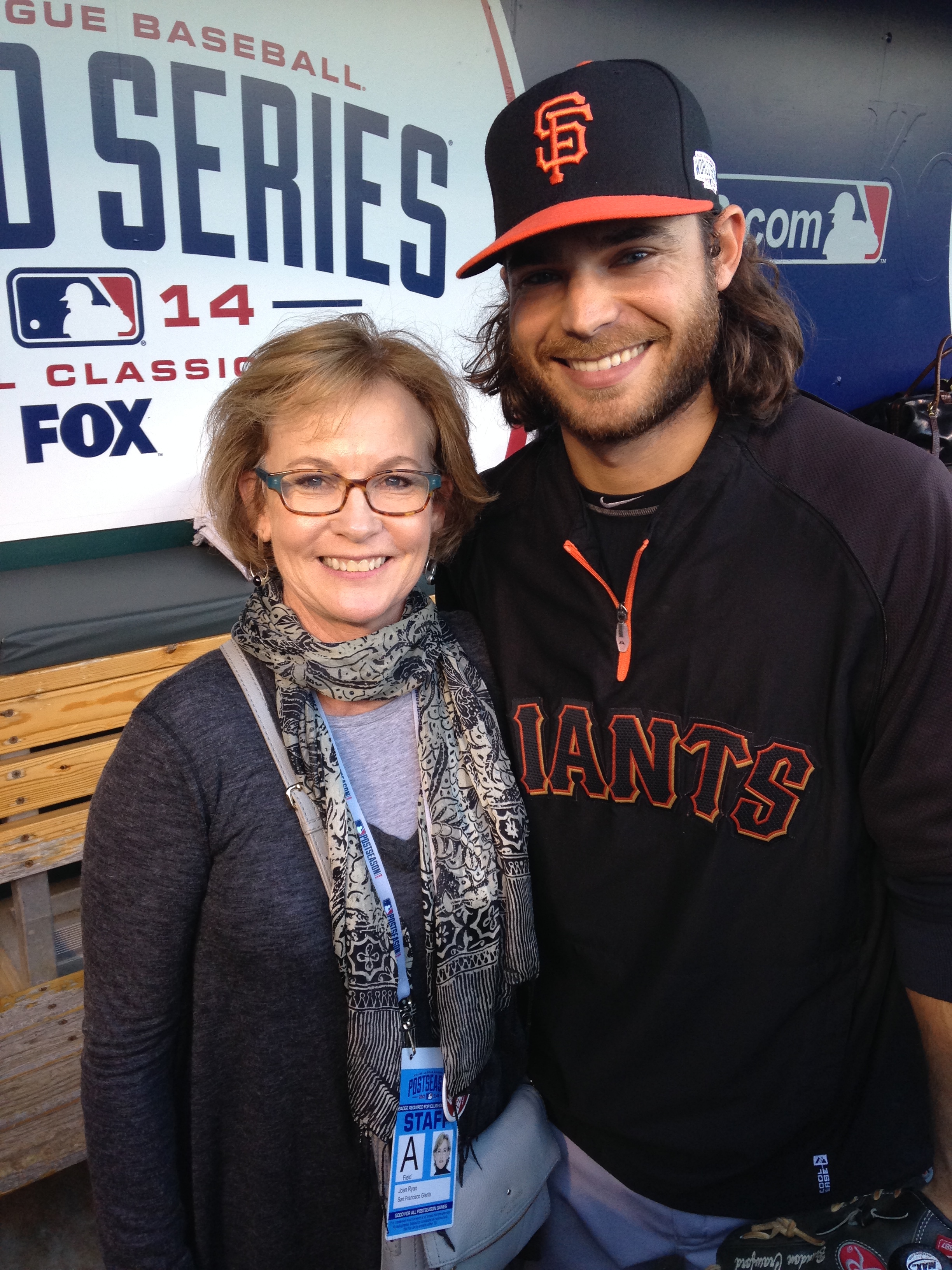

Current Career Focus

How I make my living is I work for the Giants, the San Francisco Giants, as a media consultant, so I train all the players. After being on the other side for so long, I’m helping the players take control of their own public image. I ghost write three of the player blogs, help with strategic communications in the front office and do a lot of different things. It’s really, really fun because it’s a great organization and it’s really a good group of guys. So it’s fun to be on the other side and have a little impact on how the players conduct themselves and just helping them actually grow up and make that transition from a kid to an adult professional.

A lot of the Latin players kind of don’t get enough training and attention, so I’m helping them. With all the new media, the players really need to understand how to use it and what are the pitfalls. The Giants, like most organizations now, understand that their connection to their fans is the most important thing. So how do you use it? How do the players better connect with their fans? Social media is just huge, huge, huge in that.

I just ghostwrite those three blogs. “Inside the Giants Clubhouse” was kind of an experiment, and we don’t do that anymore. It’s really Brandon Crawford and Brandon Belt, who kind of share a blog called “Brandon and Brandon.” Then the other one is Gregor Blanco, because we always have a Spanish-language player and so we do it in Spanish and in English. That’s how I ended up writing Bengie’s book because I did a blog with him for two and a half years called “Behind the Mask.”

I really thought that I’d like [teaching at San Francisco State and University of California, Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism] more than I did but I found out that I really kind of don’t. I don’t like all of the paperwork that goes with teaching. I like teaching because I love talking about writing and sharing everything I’ve learned over the years but I just don’t like all that paperwork. So I love going in as a guest lecturer now.

So that’s what I do [with the Giants] because they pay me 12 months a year. That’s kind of my base salary and then the books, which I probably spend as much time on the books as I do with the Giants. This Bengie Molina book, which should’ve taken me a year, took three years, so you end up making minimum wage when you figure out all the time you put into it. But I just couldn’t figure out how to tell it so I rewrote it three times.

My philosophy has always been that, even when I writing columns, every column should be the most ambitious one that I’ve ever written. It’s easy to be ambitious in a column or even in long-form journalism, making that the most ambitious project I’ve ever done. But when you do it for a book, if it’s going to be the most ambitious and best book you’ve ever done, it takes a lot longer. So I was working for the Giants, last year both my parents died and my son is still, with his brain injury, a handful. It’s still a lot that my husband and I have to do for him. But I’m really philosophical about it all. The book took as long as it needed to take and that’s how long it took.

Influences on Her Career

My husband definitely did [influence me] because he did so much boxing [as a sportscaster] and I ended up doing boxing for the Examiner. He really helped me a lot, just understanding the sport, getting me access to everybody he knew. So absolutely, he was somebody I could talk to about story ideas and that sort of thing.

But for some of the sports columns, when I first started, when I would be in the press box covering the Super Bowl or the World Series or these championship fights, I was in so far over my head. It was ridiculous. I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I was very eager to learn everything. I would sit in these press boxes after a Super Bowl game and I’m looking to my right and there’s Dave Kindred. To my left is Jim Murray and Dave Anderson, Leigh Montville, all these players that I so admired, and I’m thinking, “Oh my God! What am I doing in here? I don’t belong in here.”

So I used the advice that my father gave me in playing softball. I was always really short and little. He would say, “When you step on the field, you have to believe, truly believe, you are the best player out there, and you hope the ball comes to you because nobody is better equipped to catch that ball than you are.”

You hope it comes to you. So for three hours, an hour, hour and a half, or however long the game was, I would convince myself that I was the best player out there. I applied that to the press box. I would just sit there and convince myself, “You know what? I’m the best writer in here. I’m absolutely the best writer in here. I can do this.”

But to help myself, I would pretend I was Jim Murray because he really was the best writer in there. So I’d say, “How would Jim Murray write this? Or how would Dave Kindred write this?”

I would kind of pretend I was Jim Murray or Dave Kindred and almost picture their column on the page, and then it would kind of open me up to just get in their brains a little bit because they’re the best in the business. So I’d try on all those different hats and different styles all the time until hopefully, I developed my own.

Winning the Edgar A. Poe Award from the White House Correspondents Association for “War Without End”

I was writing kind of personal columns on Sundays and still doing sports and then I went into the office and starting writing news columns. Then I went out to the newsroom to be the metro columnist and do some feature stories. So this was a feature story that I was interested in.

I thought, “You know, we focus so much on the fatalities of the war and we don’t look as much on the thousands and thousands and thousands of guys and women who come back just absolutely devastated.”

So a photographer and I went to Walter Reed Medical Center in D.C. and didn’t know if we were going to do brain injury or whatever. This was before my son’s brain injury. So we ended up, long story short, focusing on the amputees. We interviewed a lot of people, hung out there a little bit and decided to focus on these two guys, both of whom were in the same Charlie company out of Fort Lewis in Washington state and within three days of each other, both of them were hit by IEDs and lost both their legs.

Two photographers – there was one photographer assigned to one guy and one woman, Deanne Fitzmaurice who ended up doing the Lincecum thing [for the book “Freak Season”] assigned to the other one. We followed them for a year in what is life like now, from Walter Reed going back to their hometowns and trying to readjust to their lives. One of them was unmarried. The other one was married with two kids.

It was just such a profound experience for me to be inside their lives, to really get to know them and what they’ve been through and what their families had been through and what they continue to go through.

Strangely enough, a year later, my own son [got injured]. Both of them also had brain injuries because the IEDs just completely rattles your brain and you get brain injuries. Then, a year later my own son had a brain injury and was on a lot of the same medications that they were on so I wasn’t freaked out that my son was in a drug-induced coma.

So people would say, “He’s in a coma?” and I’d say, “Yeah, it’s a drug-induced coma.”

He was on the same medication that I knew these guys were on, so it was really weird that I was kind of prepared in a way for my own son and his devastating injury.

Just a couple weeks ago, at the Commonwealth Club here in San Francisco, they do a lot of these onstage interviews that are then played on the radio on about 250 stations. I interviewed the Fainaru brothers who just did the book “League of Denial” so I’ve read their book. If I was still writing sports, I would be all over that [topic.] Absolutely.

Strangely enough, maybe 10 years ago, I did a book proposal called “Disposable Heroes” about football players and the aftermath, about once they walk off the stage and what happens to these guys. I did a ton of research and my agent couldn’t sell it. The publishers didn’t know who would buy this. NFL fans don’t want to know and if you’re not an NFL fan, you’re not interested, and I thought that’s probably true. So I wasn’t able to sell it.

Her Charitable Involvement with Coaching Corps, Formerly Known as Team-Up

The name now is Coaching Corps. We changed the name a couple years ago but I’m still a trustee for Coaching Corps. I’m on the board of directors, and what the organization does is it harnesses the power of sports to reach kids in low-income communities who don’t have the same opportunities to play sports. It’s not about sports. It’s about instilling all those great things you learn through sports, like playing with confidence.

(Photo Courtesy of Joan Ryan)

If I didn’t play sports, there’s no way I’d be a sportswriter. It instilled that competitiveness in me and helped me build my self-confidence, all of those things.

With the budget cuts there’s been, there’s whole neighborhoods, whole communities, where sports is just not that acceptable for them anymore. Part of the reason is that there are not enough coaches. So what we figured out is to recruit coaches from all of the universities, train them and send them out into the communities that need them the most so that every kid has that special coach, mentor, somebody who really believes in them and helps them learn all the lessons that the middle-class and affluent kids are getting.

Why do we all want our kids to play sports? It’s not because we think they will make it to the NFL or the WNBA. It’s that we know sports really shapes a kid’s character and personality and prepares them in ways that the classroom can’t.

Advice for Young Journalists

I don’t know if it’s a whole lot different now for men and women. I would probably give the same advice for both, except the one thing that I would say for women is that there are so many good role models out there now. You don’t have to be the beauty queen, the sex kitten, the one that gets attention in sports. You have to really know your business. You have to be super, super professional.

Have clarity as to why you want to cover sports instead of something else, and I would say that to guys too. Why do you want to cover sports instead of something else? It’s really hopefully the answer that you get is they recognize that as a writer, there’s just so much material. If you can’t write sports, you can’t write because you have these incredible characters to work with. You have built-in drama. Most sporting events have a beginning, middle and end and some sort of climactic moment. You know what’s at stake for each side. It has all those elements of any good story and you just have to recognize them. It’s the best material to really use your best storytelling techniques.

My advice that I would give is that a lot of people will say, “To be a good writer, you’ve just got to write and write and write,” but I always say, “To be a good writer, you’ve got to read and read and read.”

Read great stuff. Don’t just read Sports Illustrated. Don’t just read sports. Just read everything, especially fiction. You will learn more about writing nonfiction by reading fiction because fiction brings to life character better than most nonfiction dealing with real characters. It’s the fictional characters that are more real.

So you look at it and say, “Well what is it that is making that character leap off the page? What details has this writer given me? What situations have they described that give me insight into who that character is?”

Apply exactly those same techniques to nonfiction. I am a huge fiction reader. I read nonfiction mostly for work or if it’s a topic that I’m really interested in, but mostly it’s fiction.

If there’s a paragraph or a page in which in very few sentences, they just nailed it — a place or a person — I would say, “How did they do that? What did they tell me that made that one place in one paragraph be completely real to me?”

That’s what I would say. Just read and notice what the writer is doing. What information did they give you first and then second and then third? Where did they take you and why did you keep reading from one paragraph to the next? How did they launch you?

You have to understand. If you’re going to build a building and you’re an architect, you’ve got to know where am I going to put this bolt and why am I going to use this material. You have to understand it.

For a while, you can kind of play it by ear because you’ve read enough and you kind of know how it’s supposed to sound, but you don’t really understand why does it work. You’ve got to start to understand why it works and I hopefully understand how it works. I’m constantly, constantly learning, which is why this book I just finished took three freakin’ years. I’m constantly learning how to do it. I was redoing it and redoing it. I know how to write but I don’t always know how to fix it.

Advice to Professional Athletes as a Former Journalist

One advice I give them is call reporters by name. For them to try to narrow the gap between the reporter and athlete, call them by name. Treat them like people. Don’t be defensive. Don’t be suspicious. Reporters are just trying to do their job. They’re not out to get you.

I think sometimes athletes just feel like, “Oh, they’re just waiting for me to trip up. They’re waiting for me to screw up.”

Well, most reporters are just looking for a good story.

“So then, how do you tell your story?”

But then I help them recognize their story. The first thing I tell them is, “You really can’t present a good public image until you understand your own story. So who are you? What do you stand for? What is your guidance system? Then, what stories do you have to tell?”

Mostly what I do, because most of us are not good at telling stories about ourselves, and especially they’re not because they don’t think that way, is I talk to their parents and their high school coaches and their best friends and their wives, get all their stories from them, and then go back to the athlete and say, “Okay, let’s figure out your stories and how these stories represent what you value and what you stand for.”

Just like in journalism, it’s all about storytelling. It’s the same thing if you’re the interviewee. It’s all about storytelling. So I kind of enlighten them a little bit. How does journalism work? How can they best serve it for the reporter’s best interest and their own?

I tell them that they’re grown-ups now and this is a business transaction. The clubhouse isn’t their living room. It’s their office. The reporter has as much right to be in there as they do. That’s the reporter’s office too for the time that the clubhouse is open, so don’t think that they are treading on your turf. It’s not your turf. You share it with them.

So I’m bringing all those things. A lot of athletes have a real misconception about how this all works. You kind of demystify it and explain that this is what reporters are trying to do. When they write something bad, is it accurate? Well, if it’s accurate, then you’ve got no complaints. Move on. Don’t do that thing if you don’t want it written about. If you don’t want to be quoted saying something, then don’t say it. That’s not the reporter’s fault for printing it.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski Adam Schefter

Adam Schefter Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor Frank Deford

Frank Deford Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Bryan Curtis

Bryan Curtis Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga