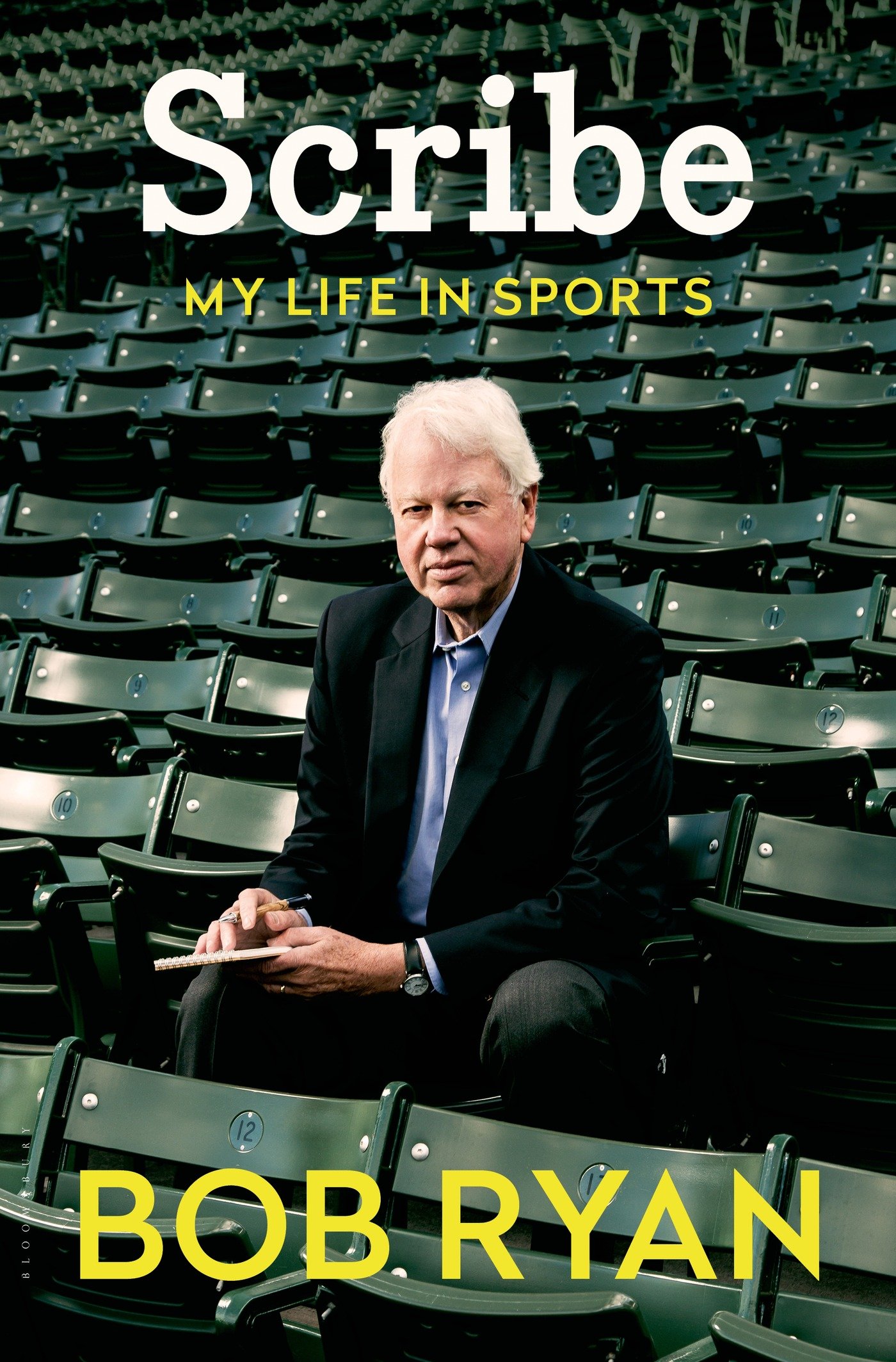

BOB RYAN

I remember reading the newspaper at home, which was a tabloid, in Trenton, New Jersey, The Trentonian, back to front, not front to back, because the back is where the sports page began, as it does in most classic tabloids, such as the New York Daily News, New York Post, etc.

I remember specifically that my father would take me, for example, to a high school basketball game, the Trenton Catholic game, which was the big deal in town in the 1950s in Trenton, on a Friday night, and that I couldn’t wait ‘till Saturday morning to read about the game.

The game was not validated in my head, was not actually officially real in my mind until I had read about it and saw what the paper had to say about it.

I needed to see if it looked like what I remembered or what I could learn about the game that I didn’t see. The idea of having it verified and validated in print was essential to the experience. That’s my earliest memory of the connection between sports and journalism.

I don’t think anything makes you want to become a sports journalist. I think you’re wired from the start to have aptitude and an interest, and I had that.

It was obviously nurtured by the fact that I was exposed to sports from the beginning. Literally from the beginning. I have no recollection of a life that did not evolve and revolve around going to local sports events, for a couple of years in the early ‘50s of going to college events because my father was working as assistant athletic director at Villanova, and then after that, going to baseball games in New York City and Philadelphia in the summer because he had connections with the Phillies and former New York, now San Francisco Giants, so we would often get to go to games.

Plus, all the local sports stuff that was going on, the high school sports were very big during the ‘50s, the basketball games I just alluded to and so forth. There was always a matter of games, games, and more games. Everything always revolved around athletic events.

I could have easily gone to Washington, D.C. I got into Boston College, Holy Cross and Georgetown, and by process of elimination I got rid of Worcester. It was nothing against Holy Cross, which I happen to like very much now, but it was a complicated story and I ended up going to B.C.

My first big moment I was broadcasting a game in what had to be my sophomore year, because Red Auerbach was there to scout John Austin, and he got out in ’66, and I just remember looking up and someone leading Red across the court at halftime and realizing they’re bringing him over to have me interview him.

So I interviewed him, and it was obviously a tremendous thrill. I’m glad I didn’t have to worry about it all day long — I probably would have pee-peed in my pants — but you have to react to the circumstance and do the job and I did and there is a couple of nice photos from the interview that I kept and I got Red to sign one of them. But you could imagine! I was 20 years old, and here comes Red Auerbach.

I got started very simply, by applying for a Boston Globe internship and being accepted. What led to that was something, but that’s how it happened, I was given the chance for an interview and I was chosen for the program and there were three of us chosen to be sport interns; a guy named Dave Martin, me and a guy named Peter Gammons — you may have heard of him.

The day we met was June 10, 1968, the first day on the job. I graduated June 3 and started a week later at the Globe and met this guy Gammons, and we got acquainted and we’ve been friendly ever since.

The interview came about because of my connection with the Boston College sports information office. I was not the official envoy, but I was an unpaid helper, and I did some things for them; therefore, I was in the loop and given the chance through their offices.

I was able to get an interview for the Globe intern program. Most internship programs are for undergraduates, not graduates, and it was a lucky break they even agreed to accept me.

I was an intern in the summer of ’68, and at the end of the summer I asked if I could remain at the Globe until I went into my active duty in the Army reserves.

I enlisted in April of that year and it was scheduled to begin at the end of October and they said “Yeah, OK.” I was basically a copy boy and covering some high school football games on Saturdays and Sundays — the local Catholic league played on Sundays in those days.

So at the end of October, I went to do my four months at Fort Knox, Tennessee, and when I came out, the Globe told me that when they got an opening they would put me on the staff, but they couldn’t put it in writing.

So from February to October of ’69 I was a copy boy, until one day, I was sitting around doing something, until one day, the sports editor came up to me and said, “You probably thought we forgot all about you, but things are happening and Bob Sales is leaving to go into news, and you're going to get the job. By the way, you’re covering the Celtics on Friday night.”

Oh, really? OK, so I had not met anybody, had not been to any exhibition games, practices, and hadn’t met Tom Heinsohn, the new coach. I had not done anything, and at the time I was a much stronger college basketball fan than a NBA fan. So I went and covered the game.

It was their season-opening game against the Cincinnati Royals, it was the first game after Bill Russell and Sam Jones had retired, so it was a whole new look for the Celtics.

Fortunately for me, the head coach for the Royals was former Celtic great and Boston College head coach Bob Cousy, which made me feel more comfortable. I got to know him in my capacity as a play-by-play broadcaster on basketball games, and writing for the B.C. school newspaper, The Heights.

The game went on, and I remember being in the locker room and interviewing Oscar Robertson of the Royals after the game, which they won by two points. I just remember thinking, “Oh my god, this is Oscar Robertson, and this is a big moment!” You got to get over that, but that’s the way it was.

I blew my first deadline. I think I was a little slow getting things organized, but they pitied me and my editors knew the whole circumstance. I never blew a deadline again after that, I can promise you.

That was just unprecedented: I was 23, and for people who don’t understand Boston, the Celtics had just won 11 championships in 13 years, but it was the farthest thing from a basketball town.

It was a hockey town, and there was no heir apparent when Sales left. He’d been covering the Celtics and nobody wanted the job or knew or cared much about basketball and people knew I was a basketball guy, so good for me.

Gammons and I split the first dozen home games or so, and then I finally fell into the job. The first year I only went to the home games and the NBA All-Star Game, which was in Philadelphia, and I wrote the away games by listening to the radio or watching them on TV when they got on, which wasn’t until after my first year. I took hold of it and things went from there.

Being impartial is a balance you have to strike. You want to gain access, have people talk to you and learn as much as you can — a degree to which really depends on how much you love the sport.

If it’s just a job and it’s not what moves or disturbs the soul or you don’t have a great particular passion for it, it’s very easy to acquire a detached viewpoint. But because I happened to love basketball, and I was learning the NBA from the inside out from these great players such as John Havlicek and Don Nelson and so forth, as well as the coach, Tom Heinsohn, who was a Hall of Fame player before he coached, it was inevitable that I was going to get close.

You just have to develop credibility; you have to show the audience you're willing to criticize the team when the time comes and not only show the difference between good and bad but good and great and not overpraise. This is all knowledge you acquire gradually.

You need time to establish yourself with people, but it’s hard not to have problems, as in my case. It turned out that Heinsohn was resentful of my relationship with the players, because he thought he had earned the right to have a closer relationship, and that was my biggest problem I faced.

The first time I saw Larry Bird play, he got a defensive rebound, advanced the ball to mid-court, suddenly rocked back and threw an underhand bullet to Carl Nicks for a layup. I’d never seen anything like that coming from a 6-foot-9 guy, and he had a good game and the game-winning basket on top of that. So I walked out of there convinced.

We had been reading about him; I took two guys with me, Jayson Stark, who you probably recognize from ESPN and Mike Madden, who later became the columnist for the Globe, who were working for the Providence Journal.

The only reason I was even at the game, in Indianapolis was because Providence was playing Michigan State in a NCAA first-round game Saturday afternoon, but on the Friday night preceding, Indiana State was playing Illinois State at home in an NIT game. So we drove out to Terre Haute — it’s only about 70 miles to the game — watched him and came back talking about Bird.

But you don’t necessarily project it to become the very good relationship that it did and I would wind up writing a book and being friendly with Larry visiting his home on some occasions. You could never expect that at the time.

By the time we got to working on the book, I had known Larry for eight years and been with him in a lot of circumstances. So I kind of had the cadence and the feel and the voice and the thought process, and I had heard all of the stories because I knew what questions to ask for the book. I was comfortable, and he was comfortable with me, it was the product of eight years of being around him.

That was the third book that I had done as told to; the first was John Havlicek, the second with Cousy, and this one with Larry. You have to figure out a way channel their voice, and the best way is to get the subject’s words verbatim as much as you can.

The No. 1 difference between sportswriters then and now is probably you can’t go out drinking with the players. Seriously! [Sportswriters] don’t associate, they don’t hang and they don’t travel with them.

We literally traveled with the players, with them on the plane, at the airport; if there was a delay, you were with them, you’d go to the bar or the coffee shop, you stayed at the same hotel, you ran into them at breakfast or lunch, you rode the bus to practice to go to the shootaround with them, and they used to hold the bus for us to get finish our stories.

I can still remember in Cleveland, Steve Bulpett of the Boston Herald, who still covers the Celtics, out in Ridgefield, Ohio, where they played at the Ridgefield Coliseum, and the team holding the bus for him because they were our ride to the airport.

That’s the way it was; there was an intimacy and a ready relationship, meaning that they understood us and we knew them as human beings, not players. We knew their families’ names, wives’ and relatives’ names. We spent lots of time with them.

I would always go in about an hour before practice and sit down in the locker room and just [talk] with these guys with no notebook, just shoot the s--- about the NBA, about college, about anything. Then I’d duck in the coach’s office, talk to him a little bit, and then practice would go on. I’d watch, and after practice was over, then I would pull out the notebook and go get the interview I wanted for the story I would write.

That doesn’t exist anymore. Nobody goes to practice, except the reporters are let in at the end of it for maybe 10 to 15 minutes, maybe watch the team shoot free throws, and they have to go grab these players and hope that they will talk to them.

There’s guys like Kevin Garnett, where you have to schedule an appointment in advance — and I’m not making that up — and the whole coaching thing is too formalized with the cameras and stand in front of the logos and all that stuff. That didn’t exist in those days; it was informal and I’d stand around after practice shagging loose balls for guys while I’m talking to them.

I remember talking to Kevin McHale one day; we were at Hellenic College, that’s where they practice. It was a Greek Orthodox seminary in Brookline, Massachusetts, where they practiced for years.

Kevin said, “Hey, come here. I want to show you something.” And I said “What’s that?” And he went and made a move. He said, “See that move?” I said, “Yup.” He said, “It’s a great move, but I can’t use it. I know they’ll call traveling, but it’s not traveling.” Stuff like that doesn’t exist anymore — nobody is standing around with the players.

There’s all these insiders — I could name 50 of them — and they’re all data-oriented and they know this and that, they are technically sound, and they break down games, and there are even guys that know people and have them on speed dial, but it’s still not the same.

They’ll never have as much fun as we had, those of us who cared. There were people that got put on beats they didn’t particularly enjoy. If you put me on a hockey beat or a football beat, I would never get into the game as much. I’d have to do my job, but I would never go into it with the passion I would go into with baseball or basketball.

When I wrote about the Red Sox in 2004, the thing about it is that the Red Sox were coming off of the disappointment in 2003, and it was similar to the World Series heartbreak in ’86.

They went back to the playoffs in ’88 and ’90, but they did not have a team that could win and everybody knew it. Oakland was better and the Sox got wiped out.

Then they played the Yankees in ‘90 and in ’95 they got beat by Cleveland, and there were hopes that year. In ’99 they lost to the Yankees in five games, and there was no question the Yankees were better.

So, now we get to 2003 and the Yankees beat the Sox in the seventh game we all know that story; Pedro Martinez staying in and Aaron Boone’s home run and it was tough.

They were better than the Yankees that year and should have won that game, and they didn’t.

I wrote a vicious, well, not vicious, but a reasonably harsh column about how everybody wanted the Yankees to face Boston and how they were failing under the circumstance. And they came back and they won.

So after the first World Series game in St. Louis, which was a close game; it was anticlimactic. But the Yankee series was the deal. You would hear people saying, “Well, if the Sox don’t win the World Series, it’s OK, because they beat the Yankees.”

But they had to win after 86 years.It was fun and historic and I was very happy to be there. I liked the team and loved [manager] Terry Francona. He’s a good man; it was fun to write, no question.

I am a writer! Look, I am a writer, and I always used to say this, when I look in the mirror, I see a writer and that is what I am. It is my best skill and that was my passion, writing. Everything else is an extracurricular activity and it could be a lot of fun. And it can also become a big financial source of income.

However, the reason people know me and why I am recognized nationally, 365 days a year, no matter where I am, is television. I understand that, and that has changed my life and all of our lives who are also lucky enough to be a part of this and changed it for a good way.

PTI is special because it only two of you and the whole format is geared towards you showing off more than any other format and I love

But I am a writer, and that is how I want to be known as. I am much happier when people recognize me for something I written verse being on TV.

I have never sat down to study a list to memorize facts. I started reading baseball books, magazine articles and stories when I was 6. Seven years old, I started cross-referencing books, things would fall into place and start to stick into my head.

That’s the reason I know every pennant winner from 1903 to now, in both leagues. It is not because I told myself, “Here is my homework for today; I am going to sit down and memorize,” like when you are forced to memorize a poem for English class in high school. I never did that and never will.

In deciding to retire from the Boston Globe in 2012, I knew. I knew. I had studied people in the business from a long way back realized that they are too many people who hang around too long, and they really do their fastballs. And it’s sad and very uncomfortable talking to them or listening to them. And I did not want to be that person.

So, No. 1, there is an expiration date, and therefore, I was thinking about that. Then I realized how much I really wanted to leave when everyone else wanted me to stay, when they thought I still had something left on a fastball and I wanted that.

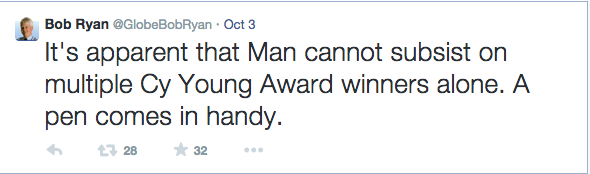

Also, it made things easier, and not staying that I left because of tweeting, but it made it easier to leave, meaning that I could not have coexisted with the phenomena of all the social media and extraneous opinions in business. Now people have to tweet during the game, which I have no interest of doing. But I would have coped with it.

So that’s why it was not the reason I left. But it made it easier to leave people I never had to worry about that stuff anymore. I never tweeted then but I tweet now. I tweet one thought a day, but it’s not a big deal.

And besides, 66 is a good social security age, believe me. So it made perfect sense. So I would quit right after the 2012 Olympics, doing something I love. I got a free trip to Europe to go on vacation from there, so that was nice. And quit doing something I like to do, and it was see you later.

The 2012 Olympics came as a good jumping-off place for me, at the right age and at the right time.

And I did not want to do it anymore. I did not have the need to go to big events anymore because I had done it. There was no serious major event that I wanted to go to. The one event that I did want to go to but didn’t was the College World Series.

Cheering in the press box? No! Well, you don’t do it overtly. The big difference is that there are people who don’t want a certain team to win and that you don’t root, in a sense. But it’s an internal matter; it’s not cheering and you don’t verbally root for a team to win.

There are people who pride themselves with their so-called “detachment,” when they talk about “I root for the story.” Well, fine! But I root for the home team to win if I happen to like the team, and at times, I do root for them.

Sometimes, I have rooted against the home team, and believe me, I do it so they can get out of my sight. But most of the time, it’s not the case. And it is a better world when the home team wins, so I feel sorry for them.

I don’t understand those people and how their minds work. The players are happier, the coach is happier, so everyone is happier. And they become better people to work with. So it’s a better circumstance when the home team wins; I have no problem rooting for a team.

I wrote often coming from a fan viewpoint: a viewpoint from the local fans and wrote in a personalized point-of-view. Some people are horrified with that but I’m not.

And the other thing that drives me crazy is that there are some people who say “Well, it doesn’t matter who wins or loses; I write about the people.” Oh, don’t give me that happy horseshit that you write about the people.

First of all, it’s not a big deal. If you are a natural writer, you are supposed to be a trained observer and gifted to understand human emotion with sensitivity and all that kind of stuff. By definition, you have to write about people. If you can’t do that, you don’t belong in the business. So it’s no big deal to me.

Try to make chicken salad meal out of a bad ballgame. Now, that is the challenge, the big writing skill, of being a writer, not writing about people. Anybody can write about people.

The strongest relationship, for the time that it occurred and the period of time of four years was Paul Silas from the Celtics, in terms of personal.

I was very close to Paul Westphal at the time as well, so those two, but Silas in particular.

John Havlicek — very friendly, but you have to understand boundaries.

Dave Cowens, who is my favorite person to write about. By far, the greatest most interesting and intriguing figure that I encounter during my writing career was Dave Cowens, who would take me on and off the court. But we are compatible and socially friendly but not that close to him.

But there was a period of time where I was close to Paul Silas. It was a valuable and important relationship for me.

When it came to Bird, I got along with Larry, but I have boundaries with Larry. I don’t try to push that I’m closer to Larry than I really am.

Now you have access to statistical information that enables you to break down a sport that was not possible during the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. We didn’t have this kind of information, so it was not there, and now we got people who make their livings doing so. Now, we have people channeling all their energy on fantasy [sports], and that is what I am talking about — they make a living providing information to people who are involved in fantasy. This all started with Bill James, who is the godfather of all of this, that journalists need to know more about a sport than any columnist, who has to learn about the whole world of sports than just learning one sport. So I look to a guy like George Shinn for information.

Back in the old days you could go out and fool the world but you can’t do that way again.

The other thing that has changed a lot is the accumulation of talk-radio and the internet with the tweeting, which has created a new forum for people.

All I know is this: is to be ready when the time comes. Now, what does that mean? It means doing your homework. The guy who succeeded me, Chris Gasper, as a good historical grasp that is better than any other reporter that I have known at the Globe. And that’s because he has done his homework. So study your history on all the major sports, including the Olympics, track and field, golf, swimming and know names.

Know names that should mean something to you. If you don’t know any, then you haven’t done your homework. You don’t know when the big break is going to come so you got to be ready when it does come.

And read! And it is not about just reading about sports, you got to read other things. You got to read the paper, front-to-back and start-to-finish, every day. And I mean the newspaper, not the Internet, because it is not all there. So you have to get the physical paper in your hand.

If there is only one magazine that you can read for the rest of your life, it is the New Yorker. If you read the New Yorker, you are going to read about everything you can imagine, including sports, and it is presented in a way that it will make you a better person for doing so. If reading is not a focal point for 365 days a year, then you are in the wrong business.

On Around the Horn, they make a big deal about me saying “You stink” to everyone. One time, someone asked “What is your favorite odor?” when it should have been “What is my favorite aroma?” The answer is the smell of bacon in the morning coming up the stairs for breakfast. But I’m not usually good with those types of questions anyways.

Michael Wilbon

Michael Wilbon Bill Nack

Bill Nack Dan Jenkins

Dan Jenkins Sally Jenkins

Sally Jenkins Jim Murray

Jim Murray Dave Anderson

Dave Anderson Christine Brennan

Christine Brennan Mitch Albom

Mitch Albom Jason Whitlock

Jason Whitlock Claire Smith

Claire Smith Bud Collins

Bud Collins Bob Ryan

Bob Ryan Joan Ryan

Joan Ryan Peter King

Peter King Wright Thompson

Wright Thompson John Feinstein

John Feinstein Lesley Visser

Lesley Visser Will Leitch

Will Leitch Tim Kurkjian

Tim Kurkjian Joe Posnanski

Joe Posnanski Terry Taylor

Terry Taylor Frank Deford

Frank Deford Tom Boswell

Tom Boswell Neil Leifer

Neil Leifer Sam Lacy

Sam Lacy Jane Leavy

Jane Leavy Kevin Blackistone

Kevin Blackistone Juliet Macur

Juliet Macur Andrew Beyer

Andrew Beyer Tom Verducci

Tom Verducci Hubert Mizell

Hubert Mizell Rachel Nichols

Rachel Nichols Dave Kindred

Dave Kindred Mike Lupica

Mike Lupica Richard Justice

Richard Justice Jerry Izenberg

Jerry Izenberg Bill Plaschke

Bill Plaschke Kevin Van Valkenburg

Kevin Van Valkenburg George Vecsey

George Vecsey Roger Angell

Roger Angell David Aldridge

David Aldridge Tony Kornheiser

Tony Kornheiser Jackie MacMullan

Jackie MacMullan J.A. Adande

J.A. Adande Robert Lipsyte

Robert Lipsyte Ramona Shelburne

Ramona Shelburne David Remnick

David Remnick Bryan Curtis

Bryan Curtis Chuck Culpepper

Chuck Culpepper Jason Gay

Jason Gay Heidi Blake

Heidi Blake Dan Steinberg

Dan Steinberg Jerome Holtzman

Jerome Holtzman Barry Svrluga

Barry Svrluga